Hello, my name is Joonshik Oh, and I’m the founder of the design organization Very Joon Oh. I’ve been working in the design field for the past 25 years. I began my career as a designer at INNO Design and later took on lead design roles at companies like Hyundai Card and Amorepacific, gaining broad experience across a wide range of projects. Through hands-on experience in frontline business environments, I’ve come to realize that design delivers its strongest impact when it’s used without boundaries—seamlessly integrated across the entire business.

Please share the most memorable experience you've had as a designer.

My most memorable experience as a designer is also the one that left me with the greatest sense of regret—and perhaps the most valuable lessons. In 2022, one of Korea’s top companies commissioned Very Joon Oh for space design consulting as they prepared to build a new headquarters. The architect, contractor, and construction supervisor had already been selected, and we were brought in toward the end of the process at the client’s request. Having worked as a design executive in multiple corporations, I had extensive experience incorporating corporate culture into workspace design, so I found the process quite intuitive. We identified the core issues, mapped out a clear direction, conducted surveys and in-depth interviews with both younger employees and executives about their vision for the company’s future workplace. The project moved forward smoothly and was incredibly stimulating.

However, there was one key aspect I had failed to prepare for—setting expectations around the project’s decision-making process. The more attention a project receives, the more stakeholders want to be involved in giving feedback and influencing outcomes. This resulted in excessive pre-meetings and constant reporting at every stage. Valuable time that should have gone toward design and execution was instead spent writing decks and responding to internal requests. The bigger issue was that everyone began sharing individual feedback—sometimes small, sometimes conflicting. It’s natural that on important projects, people want their voices heard. But in some cases, certain executives even insisted that anything they found uncomfortable be excluded from the agenda. That kind of internal filtering grew into a larger obstacle.

In the end, the project did successfully address the original issues and created clear, visible change—but due to the complications in the approval and feedback process, it left me with a sense of unfinished business. It was a project that taught me the critical importance of aligning process expectations early on, no matter how experienced or well-prepared you may be.

What is your approach when communication issues arise with clients?

When company stakeholders show increased interest in a project, it’s often a sign that the design is going well—and that level of attention can lead to better results. But only if all the requests and feedback are managed properly. There’s no single right way to handle this, but if I were to offer one piece of advice, it’s this: a slightly relaxed democracy tends to work best. If you try to equally weigh every opinion, there’s a real risk of ending up with something bland and directionless. However, from among a wide range of feedback, about 10% usually contains core values that are genuinely valuable. That’s where the designer’s ability to discern becomes critical. Although the experience I shared earlier came with some regret, it ultimately led to a much larger headquarters project, where we were again brought on for space design consulting. That’s why I’m now making more effort to minimize such issues through better preparation and clearer expectation-setting from the outset.

Is there a principle you never compromise on as a designer?

“Do the right design.” It’s even printed on my business card: Do right thinking & design. For me, it’s a declaration of intent—to use creativity as a force for positive change. When I was younger and working in corporate settings, I had a strong desire to prove myself. External validation and market response meant everything. The focus was entirely on outcomes—on driving more consumption and generating results. Now, at Very Joon Oh, my focus has shifted toward creating design that holds real value for society. When we identify the potential to embed public interest into a project, we proactively propose those ideas to the client—hoping to create positive ripple effects.

1. At Very Joon Oh, we focus on the direction of value that design can bring. 2. And we practice 360-degree design.

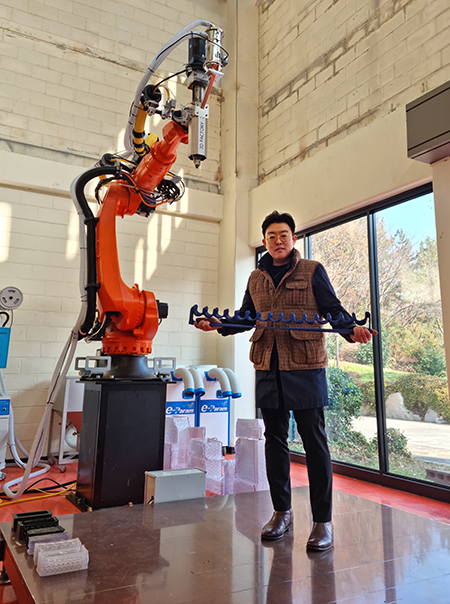

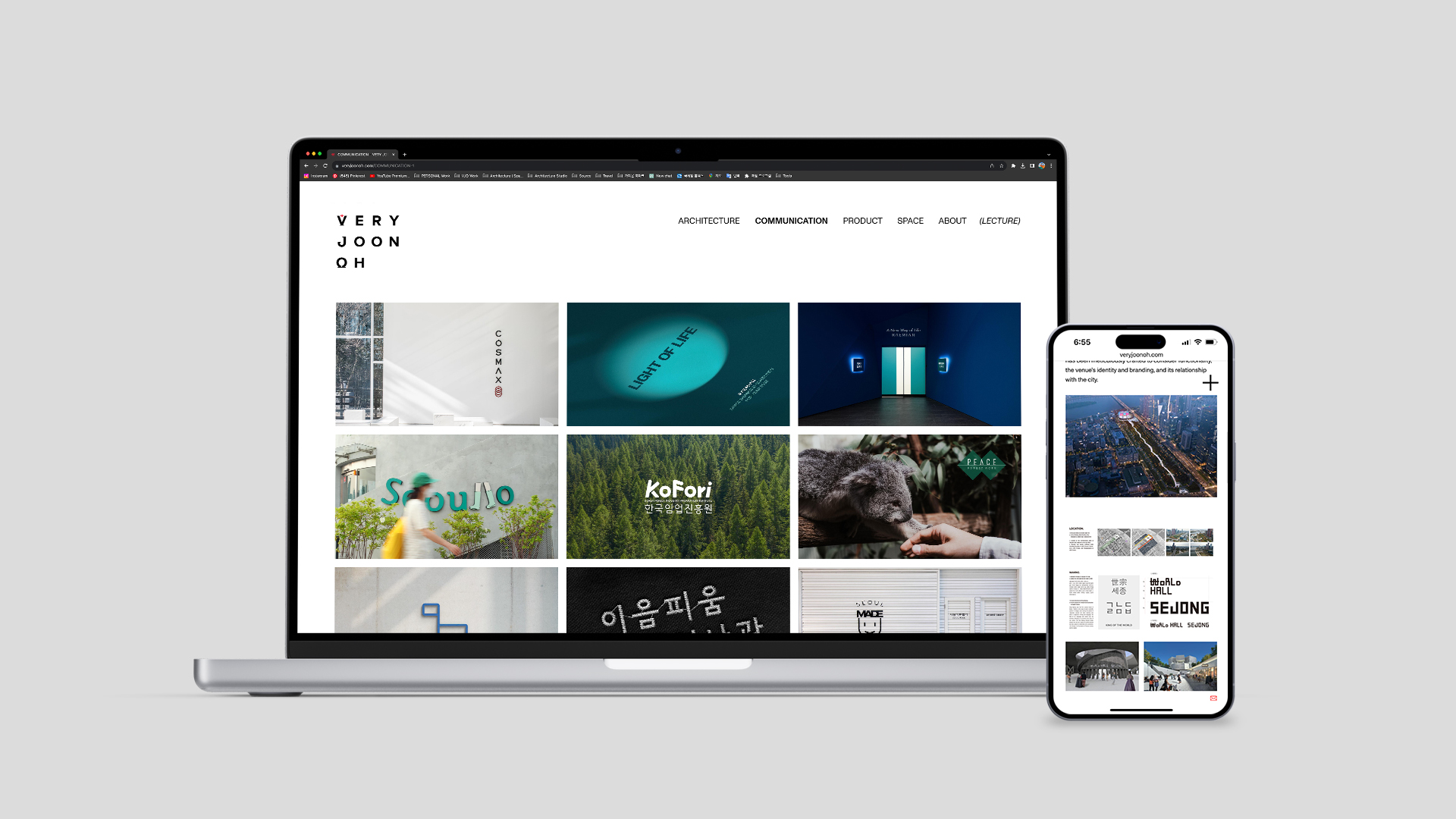

360-degree design is Very Joon Oh’s intuitive way of describing an approach that utilizes every design field to achieve a project’s business goals. It wasn’t a principle I set out with from the beginning—it’s something I grew into because every project demanded that kind of perspective. Every business needs design from multiple angles. And because society is constantly evolving, design must also expand and branch out continuously. That’s what 360-degree design represents. Currently, our portfolio at Very Joon Oh consists of approximately 30% architectural projects, 30% branding, and 30% product development. Many of these projects, although in different domains, were completed for the same client over time—making them close examples of 360-degree projects. This approach aligns our vision with that of the client toward a shared, comprehensive goal—and allows us to deliver work of the highest quality.

Is there a field you’d like to challenge yourself in, or a project you’re eager to take on?

I want to take on more projects where design can truly make a difference—fields where it can contribute to society. One example is Korea’s election culture. I’d like to elevate the quality of design in this space. Political communication, especially in legislative and presidential elections, needs a new design approach. I believe changes in communication methods can lead to changes in politics. Every election season, roads across the country are flooded with banners and posters. Not only is the design problematic, but this also generates an enormous amount of waste. It’s ironic to see campaigns promoting sustainable futures while contributing to environmental harm. That needs to change. Another area I’m deeply interested in is public architecture. While public buildings are physical spaces, they’re also platforms for design communication with citizens—a kind of civic brand space. Due to the way architectural education is structured in Korea, public architecture often gets weighed down by abstract narratives. But our times call for practical, socially conscious design. It’s time we focus on design that truly serves society.

What draws you to public design?

We develop our sense of culture and social behavior through our environment, which is why public design is so important. One example I often think of is the mascot design for the Korean National Police Agency. It was created with the intention of making the police seem friendlier, less authoritarian—but in reality, the core role of the police is to protect public safety. We don’t need a cartoon-like image for that. When design is applied, it must align with the purpose and domain. A police image should inspire both reliability and strength. But instead, across many public sectors in Korea, we’re flooded with wide-eyed, smiling cartoon characters—which I believe is far from the right direction for advancing public design.

Another area that needs change is local government council design. Why do all local council members wear the same gold badge as the National Assembly? Look closely—it’s the same badge, except for the Chinese character in the middle. Why are we still using Chinese characters in these official symbols? And why do all council chambers mimic the authoritative layout of the National Assembly in Yeouido? Spaces meant for citizens are stuck reproducing outdated traditions. It’s time we update designs that continue to exist under the passive acceptance of inherited authority. Public design must evolve to reflect modern values and real civic needs.

Do you have a personal philosophy or belief as a designer? And what is your vision for the future?

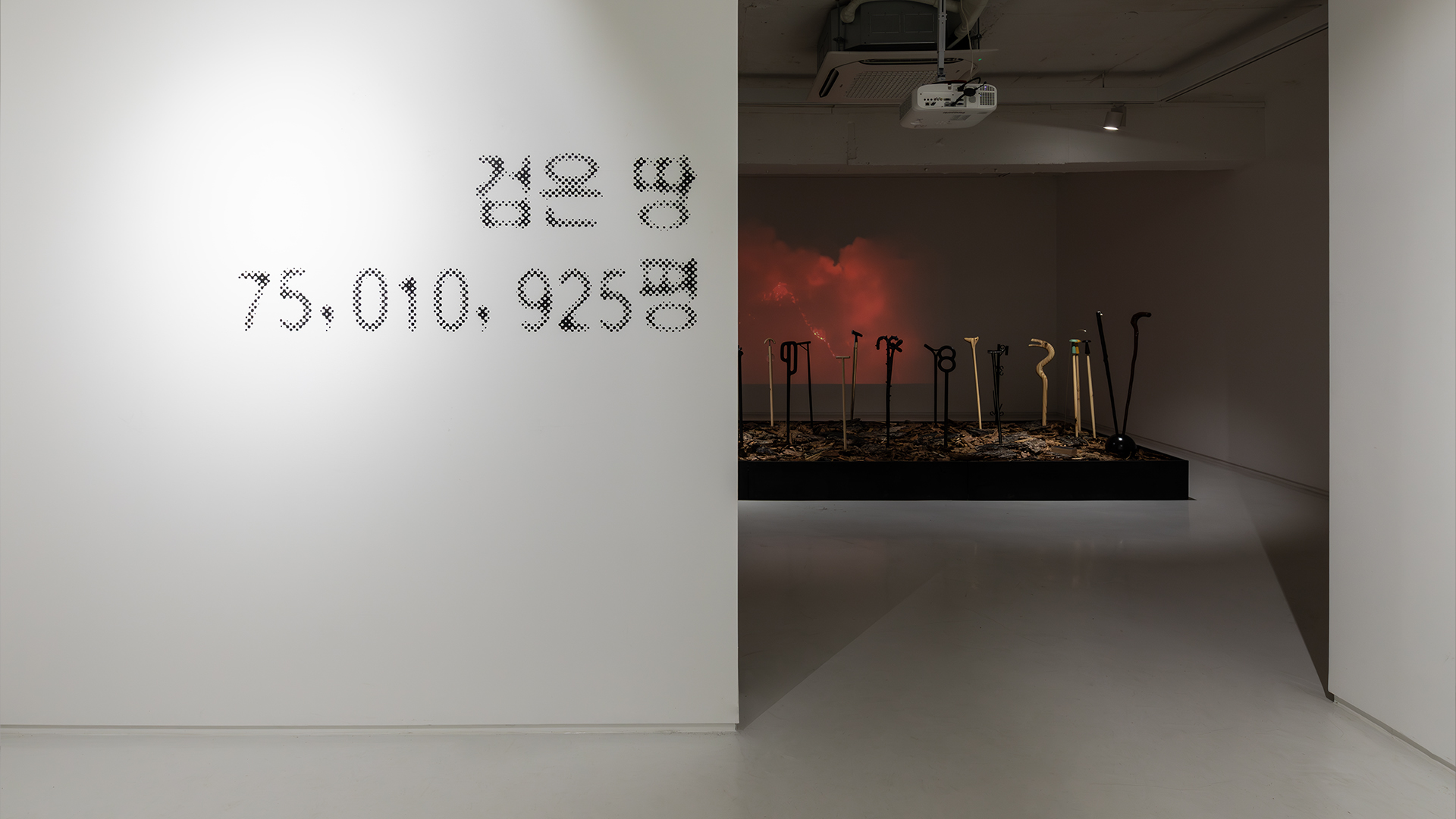

Design is like a double-edged sword. I hope that at least part of my design work can be used to help restore balance in the world. I truly believe that can lead not only me, but many others as well, toward a more joyful and harmonious environment. One experience that comes to mind is an exhibition I recently planned with alumni from the Department of Woodworking and Furniture Design at Hongik University. The project centered on repurposing pine trees that had been scorched by wildfires in Gangwon Province. It all began in 2022 when members of the Korea Forest Service told me about the damage caused by the wildfires. Centuries-old Korean red pines, known as Geumgangsong, had been lost and were being sent to firewood factories. They asked me if there might be a way to preserve or honor these trees through design.

I shared the idea with my alumni network, and the project came together rapidly. We designed and crafted walking canes using the burned Geumgangsong and held a group exhibition in collaboration with the nonprofit Peace Forest and the Honglim alumni association. As the exhibition came together, current students joined in voluntarily, and many companies reached out to support the effort. The awareness around the wildfires and the value of conservation grew, eventually leading to second and third rounds of exhibitions and partnership projects. It was a moment that reminded me: when the public resonates with a cause, design can be the medium that carries that emotion, bridges the gap, and makes real impact. That’s the kind of design I want to pursue moving forward.