A Landscape of the Past

The design industry has always stood at the crossroads of technological change. Much like resetting the origin in a 3D modeling program and realigning the axes, each era asks designers to establish a new starting point. On the eve of the iPhone, studios were building PMPs, electronic dictionaries, a wide range of mobile phones, and pocket digital cameras. I vividly recall walls layered with sketches of keypad layouts and mini QWERTY concepts, and desks crowded with hinge prototypes and ergonomic key arrangements for handheld devices. When the iPhone arrived, the origin of our thinking shifted almost overnight. Many physical products disappeared as their functions collapsed into a single device. Capacitive touchscreens and new UI frameworks ushered in a generation of buttonless objects, forcing designers to reimagine physical space and to structure meaning on empty surfaces. The touchscreen revolution did not simply remove buttons; it recast product aesthetics and architecture, drawing form away from complexity toward purposeful simplicity.

Eventually, products did more than integrate functions; they fused with services. Within the hardware of smartphones, apps, social media, and streaming became central to the user experience. Designers evolved into authors of digital services and interfaces. Whereas “product design” once meant shaping tangible objects, today the term often refers to UI, UX, and service systems. Coming from a background of sketchbooks and tactile prototypes, I still find it slightly disorienting that “product design” now points so often to the digital realm.

Between Imitation and Creation

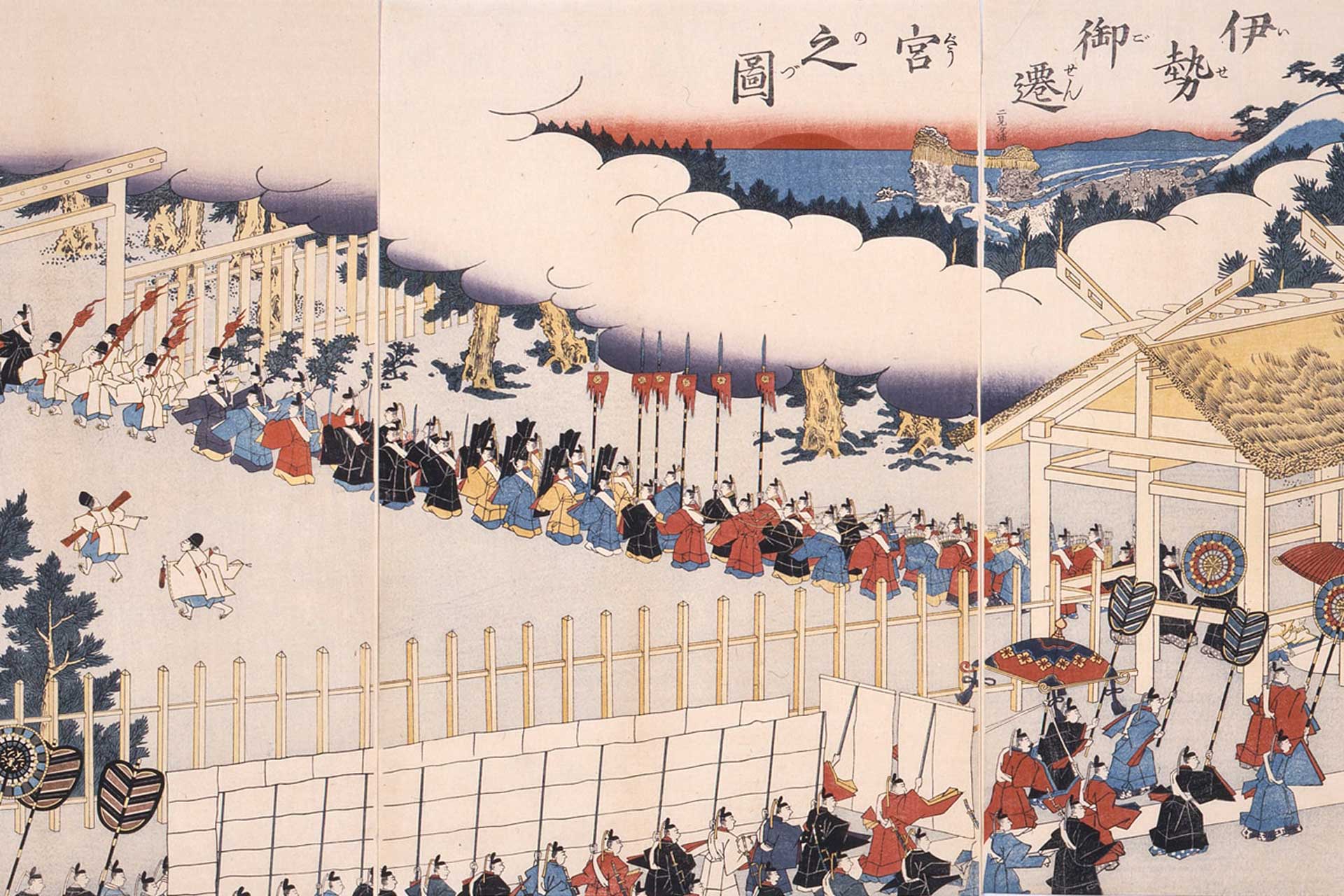

Yet the design of physical things has never disappeared. In fact, as manufacturing centers shifted to Asia, global attention to Asian design has grown. For decades, Asian design was framed as a consumer of Western originality, a follower of references. Now Asian designers are searching for new paradigms of creativity, a challenge that aligns closely with the questions AI raises about originality. In a world where AI can generate outputs effortlessly, what does originality mean for designers? The Chinese term “Shanzhai (山寨),” once used to denote counterfeits, has been reinterpreted by philosopher Byung Chul Han as a distinct form of East Asian creativity. In his book Shanzhai: Deconstruction in Chinese, Han argues that, unlike Western philosophy, which prioritizes the unchanging and the original, Chinese thought embraces change and process. Within this framework, shanzhai is not a forgery that destroys the original but a practice of constant mutation, playful transformation, and what Han calls “decreation.” A striking example he discusses is the Ise Grand Shrine in Japan. Rebuilt every twenty years for more than 1,300 years, the shrine embodies identity not through the preservation of a single original structure but through the act of continual renewal. In this tradition, the replica becomes the original. This view contrasts with Western conservation practices that emphasize authenticity and restoration.

Does this fluid generativity resemble the unchecked replication of AI? Consider the recent trend of generating Ghibli style images with AI; the phenomenon echoes shanzhai as play. Users remix familiar styles into new images and share them as creative expressions. Even so, we must distinguish between individual play and professional design, which is an act of responsibility bound by context. Shanzhai creativity is conscious and relational. It deliberately distorts or fuses references and creates new meaning through variation and reinterpretation. By contrast, much AI generated content lacks transparency. It recombines vast data stripped of context through statistical methods and masks the original creators behind the material. The tool may be fun, but it risks erasing the labor and ethics embedded in the sources. Designers in particular need to stay alert to this. When professionals use AI uncritically, they can turn playful creation into ethically hollow plagiarism. It is true that real world shanzhai also raises legal and ethical issues. Yet Han’s insight invites us to move beyond a simple binary of imitation and originality and to see creativity as process and transformation. In this age of AI, shanzhai poses a philosophical question: what does it truly mean to create?

The Next Technological Threshold

Today, designers stand at a new threshold: AI. Once again the axes feel as if they are shifting and we are returning to a new origin. A similar moment unfolded in the 1980s when CAD first entered design education. Sociologist Sherry Turkle noted the enthusiasm of students embracing digital tools and the hesitation of faculty who feared the loss of hand drawing and analog thinking. The current debate over AI echoes that divide. Just as CAD disrupted established workflows and roles, AI is doing the same. Designers may feel uneasy as familiar processes are challenged and job boundaries blur. Anyone can now generate high quality visuals from a prompt, and some studios even highlight their use of AI in portfolios. Caution is warranted. AI is a powerful tool, not a substitute for creative responsibility. It can support a process, but it cannot assume responsibility for an outcome.

As Byung Chul Han suggests, the sacred aura of originality may be fading, yet that does not absolve us from the ethical weight of authorship. In shanzhai, creativity carries traces of viewers, imitators, and alterations; decreation is grounded in awareness. AI, by contrast, tends to erase those traces. The issue is not a simple lack of originality but the absence of process and memory. Without them there is no author who can be held accountable. Paradoxically, this technology may free designers to focus more deeply on what matters: social context, detail, and philosophy. The evolution from CAD to AI opens space for the field to engage larger responsibilities such as climate change, supply chains, accessibility, and diversity.

The Final Author

In the AI era, designers cannot stop at prompt writing. AI can execute instructions, but only the designer can judge their meaning. Every output demands critical review: What data trained this model? Where might bias or uncredited appropriation be hiding? How do we ensure we are not infringing on someone else’s creative labor? Generative AI is a powerful aid, yet it can also flatten design and make everything look the same. Designers must keep questioning, resist complacency, and remain constructively skeptical. The final judgment is still human. Designers are the last line: the people who infuse results with meaning, ethics, and emotion. The questions cannot end at what a product does; they must extend to what it collects, how it interacts with people, and what kinds of ethical relationships it creates. We are standing at a new beginning, another origin point. For Asian designers, this transition is even more pronounced. With a rich manufacturing base, fast-growing technology, and distinct cultural contexts, Asia is well positioned to set new standards for ethical and creative leadership. It is no longer about following global trends, but about defining them.

So where should we place the next point on the design axis?

What coordinates will define our next leap?

The origin point of creativity is not fixed.

Each designer must reanchor themselves again and again, critically examining what technology offers and setting new coordinates with responsibility and intent.