I believe the act of purchasing can largely be divided into two categories: purpose driven purchase and value oriented consumption. As the term suggests, a purpose driven purchase is made for a clear and specific reason. For example, when the weather turns cold and you need clothes to keep warm, or when summer arrives and you plan a beach vacation but realize you do not have a swimsuit, so you buy one. In other words, it is a purchase made because not buying the product would cause obvious inconvenience. This type of purpose driven purchase took clearer shape with the rise of the capitalist market. Of course, transactions between producers and consumers existed long before that, but once capitalism took hold, producers organized as companies began manufacturing goods for profit, and consumers purchased them with money. From that point on, companies actively produced products that directly responded to people’s needs. It is no exaggeration to say that, in the early capitalist market, most products were created primarily for these purpose driven purchases.

When we look closely at products sold for clear purposes, the standards that drive a purpose driven purchase fall into two factors: price and quality. This is easy to understand. Imagine buying rice for daily meals. Which would you choose? If higher quality rice is available, even at a higher price, you may pick that. But if you are choosing between the same variety, you will likely buy the cheaper option. The same logic applies to coats. If a better quality coat is available, you would prefer it. If two coats are of identical quality, the less expensive one becomes the natural choice. This is why companies work constantly to improve quality while lowering prices: only by doing both can they win consumer choice.

However, a major problem has emerged: as technology has advanced, quality has become standardized across many products. Take cosmetics as an example. In the early days of the industry, a manufacturer’s technical capability could be a decisive edge. Today, cosmetic technologies have improved to the point where most products on the market are quite good. While cosmetics are only one example, this holds for many goods that do not require highly specialized technology, and the quality available in the market tends to be very similar. Even if subtle differences exist, ordinary consumers find them hard to perceive. Some companies do lower quality to sell at a cheaper price and compete on cost alone, but such cases are exceptions. Overall, as product quality has grown more uniform, companies face a dilemma.

The dilemma is this: if they do not lower prices further than competitors, they struggle to win over consumers. This pushes companies to discount more and more. For consumers, that may look beneficial. For companies, the story is different. If a rival selling a similar quality product cuts price, we also feel compelled to discount to avoid losing customers. Mutual discounting escalates into price competition, and eventually price wars. The result is that even selling more units does not necessarily yield higher profit, because lower prices erode margins.

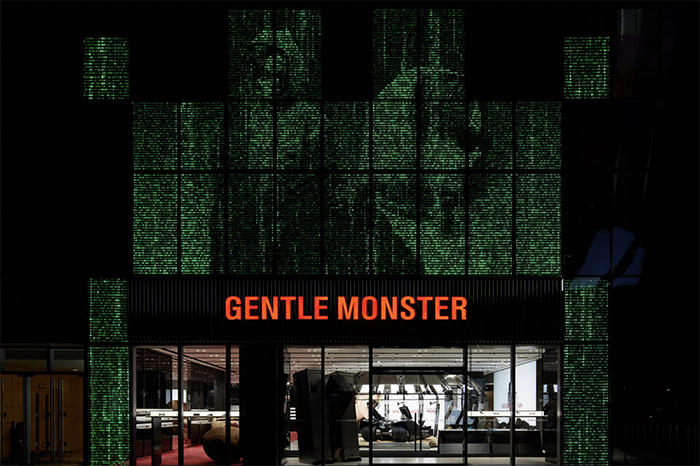

At this point, the idea of value oriented consumption emerges as a way out of endless price competition. What is value consumption? It is when companies infuse their products, and more broadly their brands, with a value that competitors cannot replicate easily, and consumers choose to purchase not only the product but also that value. In the end, value consumption means people are buying not just an object but the meaning, philosophy, or identity attached to it.

< Image source: Evian >

To illustrate this idea more clearly, let us take the bottled water market as an example. The reason I choose water is because it is a product that is colorless, tasteless, and odorless. I would assume that few, if any, readers can truly distinguish the taste of the many bottled water brands available on the market. In fact, water as a product lies at the very end of the spectrum of purpose-driven purchases—there is virtually no difference in quality between brands, and we buy it simply because we are thirsty and want to drink.

In practice, this often means that people choose either the cheapest bottled water available or a brand they are already familiar with. Now, let us think about Evian. In Korea, Evian is priced higher than regular bottled water. Yet, despite the higher cost, there are still people who choose Evian. Considering that water is one of the closest examples to a purpose-driven product, this might appear irrational. Why, then, do consumers continue to buy Evian? It is because Evian carries something beyond the basic purpose of quenching thirst—it has cultivated a luxurious image that no other bottled water brand possesses. Over the years, Evian has consistently invested in marketing strategies to embed this unique value into its name. As a result, despite its relatively high price, people continue to purchase it.

In this way, companies have come to realize that instilling such value into the name of their products is one of the ways to protect pricing power and avoid price wars in an era where quality has become standardized. Marketers began to recognize that consumers would make choices based not only on price and quality, but also on intangible values attached to the brand. Thus, branding emerged as this act of embedding value into a product or company’s identity—a way to transcend the limitations of price competition. Ultimately, branding is the deliberate creation of a unique value that sets a company apart, and it has become a powerful weapon that enables businesses to rise above the battlefield of price.