I’m Yuhei Ito from TBWA\HAKUHODO. Currently, I serve as the lead art director in an organization called Disruption Lab. Throughout my career, I’ve specialized in art direction and creative direction within the advertising field, working on communication strategies for clients such as UNIQLO, Nissan, Adidas, and 7-Eleven. What I value most in my work is this question: How much can the social perception or position of a brand or product be positively transformed before and after the design is released? The greater the change, the more challenging the task becomes—and that challenge is what makes the work truly rewarding. Conversely, I believe that in today’s world, design that fails to bring about tangible change in society lacks persuasive power.

Let me share the story of SHELLMET, a project we planned and produced (known as HOTAMET in the Japanese market).

In Sarufutsu Village, which boasts the highest scallop catch in Japan, there was a major issue: approximately 40,000 tons of discarded scallop shells were piling up each year. Each shell, when left untreated, carried trace amounts of cadmium—a heavy metal. Experts warned that as these shells accumulated, the cadmium could become concentrated, posing risks of contaminating groundwater and soil, thus creating serious environmental concerns for the region. We asked ourselves: Could we transform these discarded shells from “waste” into a new “resource” and contribute to a circular economy?

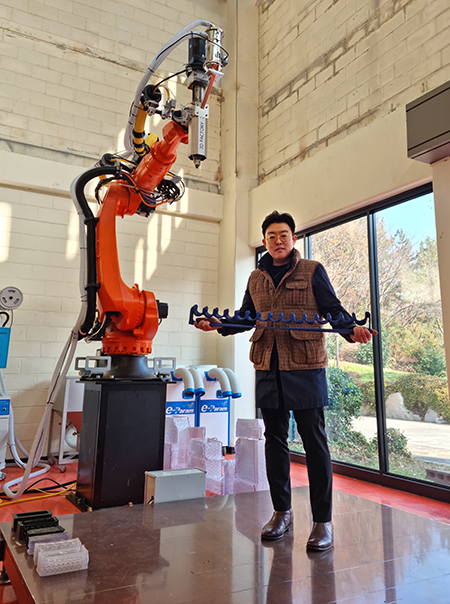

Partnering with Koshi Chemical Industry, known for their advanced eco-plastic technology, we developed a new material called "Shellstic" by mixing recycled scallop shells with plastic. Using this material, we designed a helmet for scallop fishermen.

Why a helmet? Scallop fishermen routinely wear helmets to protect themselves from falls on the boat. We thought—what if the helmets worn by these fishermen could be made from the very shells of the scallops they harvest? This idea formed the core of our concept: “Shells that once protected themselves from predators are now reborn to protect human lives.” This vision drove the project forward.

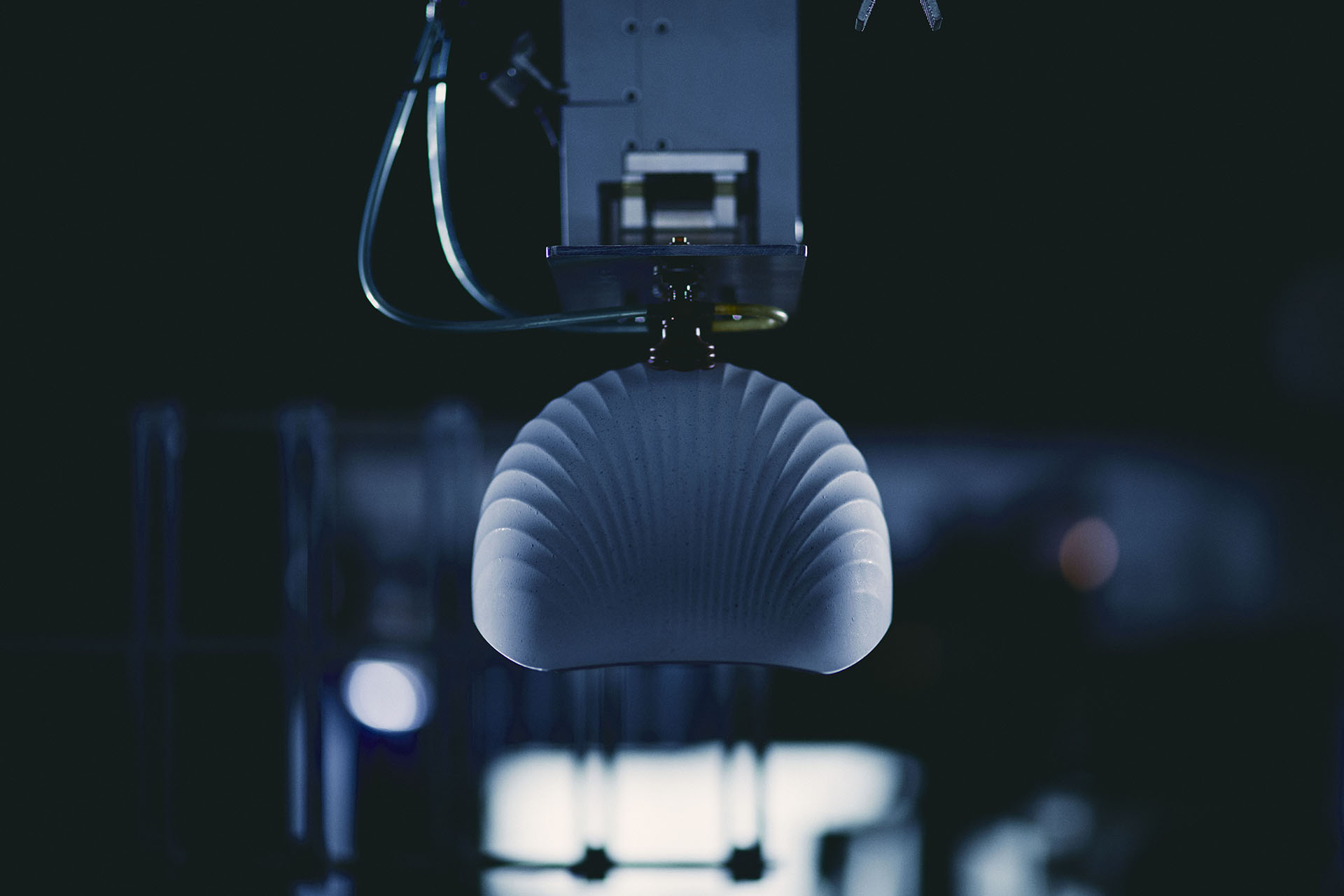

What we focused on most in the design of SHELLMET was the special ribbed structure inspired by the concept of biomimicry, specifically mimicking the structure of scallop shells. Thanks to this ribbing, we achieved approximately 33% higher strength compared to conventional helmets. Although the helmet was originally conceived for fishermen, the project gained significant attention both domestically and internationally through successful PR efforts, ultimately reaching a wide audience. As a result, SHELLMET was selected as the official helmet for the Osaka Expo, invited for exhibition at the MAAT Museum in Lisbon, Portugal, and even received an exhibition offer from the National Museum of Singapore. These developments drew considerable attention.

Moreover, the publicity surrounding SHELLMET also brought focus to the material used—"Karastick" (the scallop shell-plastic composite)—and we received numerous inquiries from companies interested in using it in their own products. We even received collaboration offers from as far away as Chile, and several projects are now underway simultaneously. If the use of this material continues to scale, we will be able to truly transform discarded scallop shells into valuable resources. Through this experience, we have become convinced that the vision-making and communication skills we’ve cultivated in advertising production can be applied and expanded to solve social issues as well.

Could you tell us about your design process? If you have a unique approach, we’d love to hear about it.

I often begin the design process by envisioning a “single image of the future.” This means imagining what kind of object or world would ideally exist down the road. I might sketch it by hand or build it out as a rough draft. It doesn’t come out perfectly from the start, but through team discussions and understanding the core issues, I try to gather all relevant information and ideas into one visual frame. From there, I repeatedly refine the image, eliminating the unnecessary to let the core concept emerge. This “one-image thinking method” has helped me direct a wide range of projects—from commercials to graphics, product, and spatial design—regardless of category.

Especially for projects outside the conventional scope of advertising, where many stakeholders might not speak the same professional language, a clear visual helps align everyone. Rather than presenting long pitch decks, one powerful image can guide the team with clarity, reduce communication costs, and increase efficiency.

Who is the designer you respect the most, and how have they influenced you?

I deeply respect Mr. Kashiwa Sato of SAMURAI. As a senior art director at Hakuhodo, his work not only showcases beautiful design and structural thinking, but also often creates significant social impact—transforming the values of companies and products he works with. What’s especially remarkable is his continued presence as a leading figure in art direction since my days as an art university student. From his total direction of 7-Eleven’s private label products to the branding of Uniqlo, Rakuten, TSUTAYA, and Kura Sushi—Mr. Sato has led major reforms for brands we encounter daily. His contributions have undoubtedly elevated the social status of art directors in Japan.

I’ve also been greatly influenced by the breadth of his creative work, which ranges from logo design to the direction of offices, factories, and even amusement parks. Whenever I take on a new project, I aspire to approach it with the same ambition and scale that Mr. Sato exemplifies.

What do you think the design industry will look like in 10 years?

I believe it's inevitable that designers—whether in graphic, product, or architecture—who cannot plan and execute their work within a sustainability-conscious, environmentally responsible framework will no longer be needed by society. In Japan today, sustainability is often discussed as a “question” within projects, but in reality, business tends to move forward by settling on “compromises.” However, in the future, this mindset will become far more rigorous. Designers will likely be expected to upskill in fields like environmental science and economics. In our own team, for example, we regularly hold study sessions on environmental management.

Moreover, with the rapid advancement of AI, the barrier to "creating" is lowering year by year. As a result, the act of making something will increasingly require designers to take greater responsibility. The title “designer” will evolve to describe professionals who not only create, but who are accountable for the impact of their work. Accordingly, the criteria by which designers are evaluated will also change. The key question will be: how well does the designer understand the cultural and societal context of the times, and how directly and positively can they create change?

Additionally, I think the field of design in medical and welfare services in Japan will gain much more attention in the years ahead. Design is an incredibly powerful tool for solving social issues, and I believe the younger generation understands this at a higher resolution than we ever did. That’s why I expect to see an influx of creative, actionable ideas addressing Japan’s aging population and related challenges.

Do you have a personal philosophy or belief as a designer?

My core belief is this: “The canvas of an art director is society.” In other words, design should not end inside your desktop. To be more specific, designs that look perfect on the artboards of Illustrator or Photoshop can often feel weak once they step out into the real world. This is something I’ve experienced repeatedly in my career—and ironically, it’s a trap that designers with strong technical skills, especially those from art school backgrounds like myself, are most likely to fall into. That’s why I always approach my work with the intention of creating designs that have both strength and flexibility, allowing them to interact with people and society, and to spread organically through others’ hands. A design that has "intentional gaps" yet maintains integrity is, in my view, the kind that can withstand the test of time and won’t be easily consumed or forgotten by trends.

Even in the planning stages, I constantly ask myself and my team: Will this design still matter 10 years from now? Will the people who operate or manage it feel empowered and happy? By confronting these micro and macro questions, I aim to rigorously test whether the work can be accepted, sustained, and expanded by society.