Direrector Sil Jin Founder of CUZ

“Media art has entered an era in which it no longer remains something to be merely viewed, but functions as an environment capable of shaping human emotion and states of perception. The question of whether a screen can move beyond being a window for information and become a space for presence, breathing, and recovery is one that media and design must now confront together. In this interview, we discuss CUZ’s perspective on the role of media art, the experiential differences created by large-scale installation media, and the enduring essence of design as the act of shaping human states, even amid rapid technological change.”

Could you begin by introducing CUZ, including when the group began its activities and what meaning is embedded in the name “CUZ”?

CUZ is a media art group that connects space, emotion, and technology through media based practices. Rather than producing content meant simply to be watched, we design how people sense, feel, and transition into different states when they enter a particular space. Our practice began with large scale screen based media art and spatial projects, and has since expanded into digital signage, interactive media, and wellness oriented content. The name CUZ originates from the word Because. We always begin our work by asking why this experience is necessary. We seek the moment when that question leads to a shift in human emotion and perception.

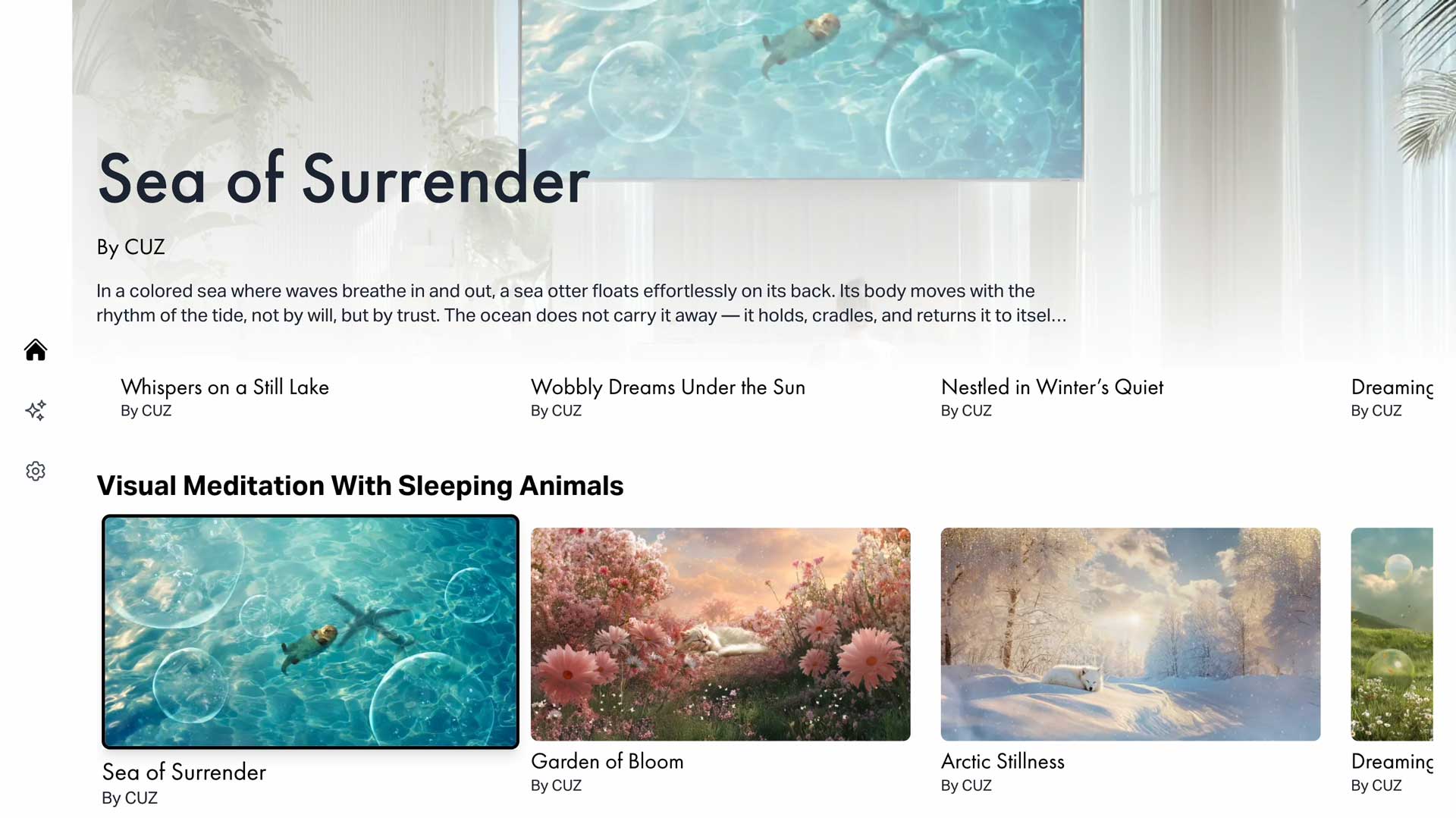

What ideas led to the launch of the “Visual Meditation” project in collaboration with Samsung, and what does this partnership represent within CUZ’s media art philosophy and approach to brand collaboration?

Visual Meditation began with a very clear sense of inquiry. I believe that art, including media art, is fundamentally a medium that enables healing and reflection. However, within today’s rapidly changing environment, we rarely have time to look inward or restore our senses. Screens, in particular, are something we face all day long, yet they have largely functioned as tools that demand information consumption and judgment. The realization that we spend the entire day looking at screens without ever truly resting was the starting point of this project. Visual Meditation was an attempt to transform the screen from a window for content into a space for breathing. Through visual elements, color, and movement, we designed the experience to naturally stabilize the user’s breathing and emotional state. Rather than something to be watched, it is closer to an experience of staying and recovering.

The collaboration with Samsung was not simply a brand partnership for CUZ, but a turning point that allowed media art to enter everyday devices. It was an experiment in allowing media art to permeate personal living spaces and daily rhythms, rather than remaining confined to exhibitions or specific locations. In that sense, it directly aligns with CUZ’s philosophy of designing sensory experiences within everyday life.

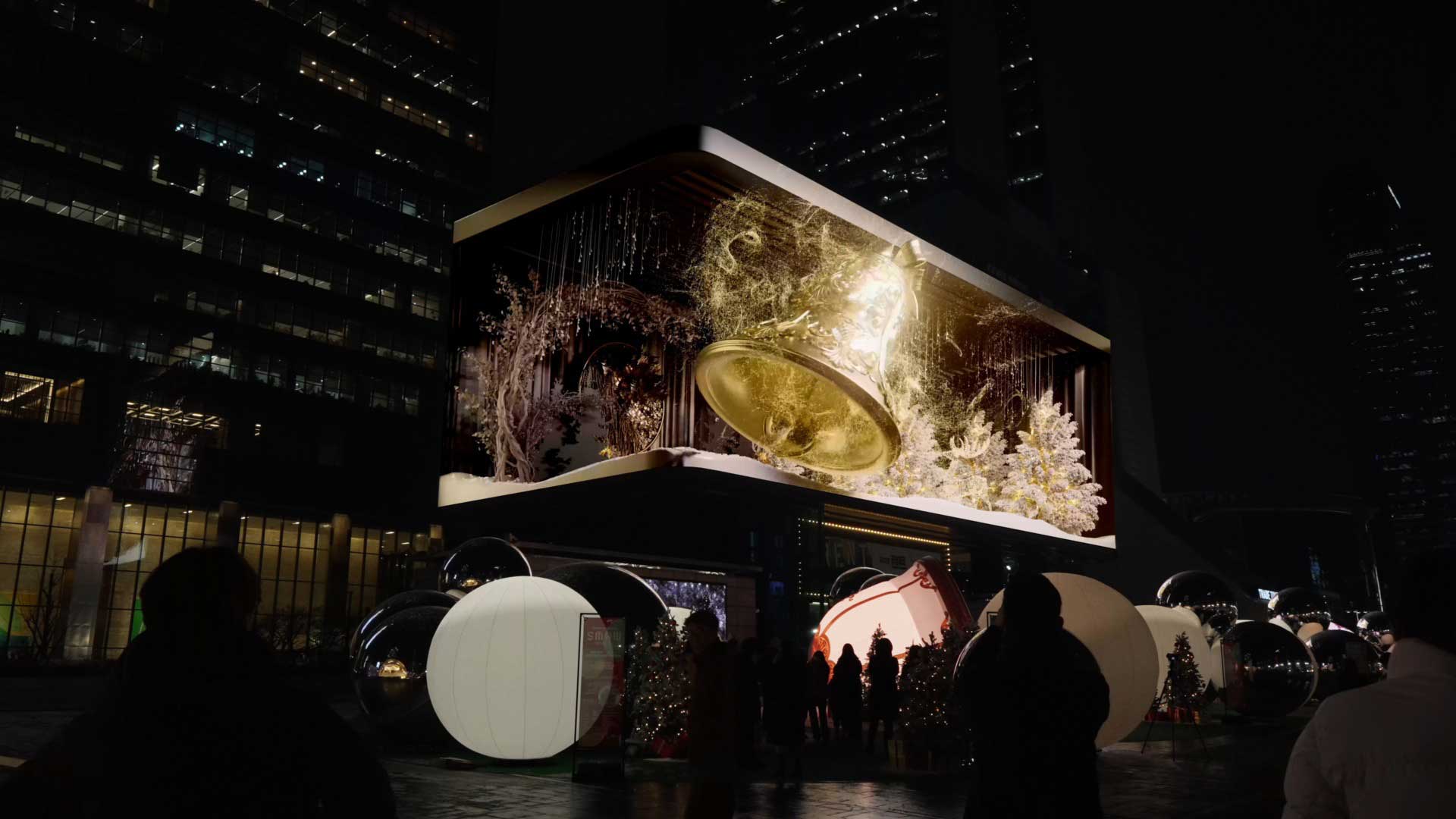

CUZ has produced media art projects for building facades and large scale screen installations. How do these large scale installations differ from conventional video or motion design projects in terms of the experiences they create?

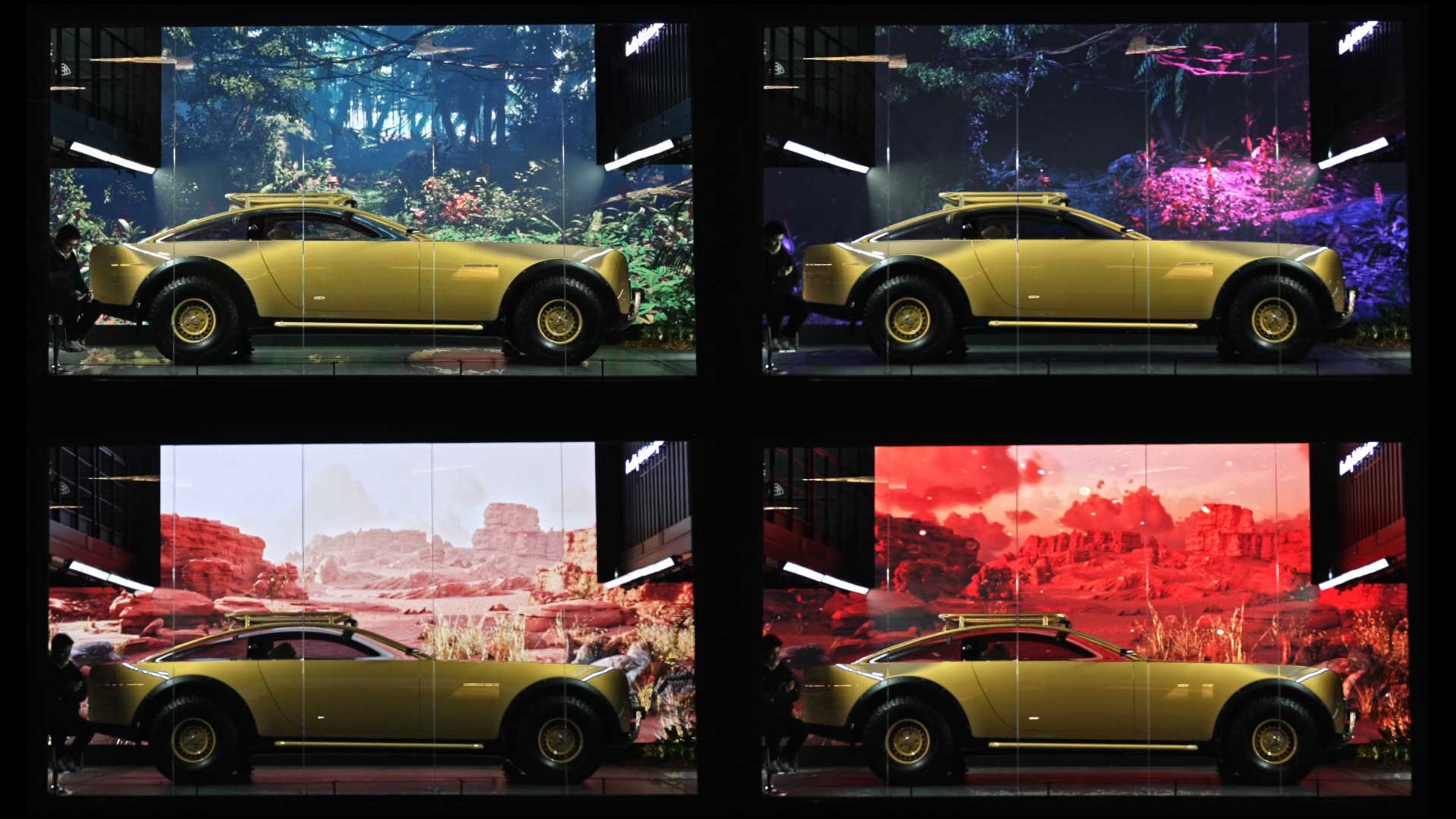

CUZ’s large scale media art projects for building exteriors and major screens are not simply expanded versions of video, but works that reconfigure an entire space into a sensory environment. We do not treat the screen as an isolated medium, but as part of an experience integrated with the city, architecture, and human movement. Compared to conventional video or motion design, these installations create three clear distinctions. The first lies in emotional impact. While standard video delivers emotion within the frame, large scale installations stimulate emotion spatially through scale, light, and rhythm. Viewers experience not so much watching the image as being inside the scene. The second difference is in the mode of experience. In large installations, viewers are not fixed spectators but moving or lingering bodies. We design rhythms and loop structures that account for both brief glances from passersby and longer engagements from those who remain, reducing fatigue even in repetitive exposure environments. The third difference concerns memory formation. Whereas conventional motion design leaves memories of the content itself, large scale installations leave memories bound to place. Viewers tend to remember the atmosphere and sensations of the space rather than a specific image, transforming the space itself into a brand impression.

From the earliest planning stages, CUZ considers installation environments and operational conditions, including day and night cycles, ambient light, viewing distance, and repetition. Our goal is not momentary impact but spatial experiences that continue to function over time. Ultimately, CUZ’s large scale media art is less about expanding images and more about designing environments where brand and space are perceived as a unified sensory experience.

When collaborating with brands on media art projects, what design considerations do you regard as most important throughout the process from planning to installation and ongoing operation?

CUZ approaches brand collaborations not as single projects but as processes of designing and sustaining an experience. From initial planning to post installation operation, we integrate the entire process into a single design flow. The first and most important consideration is establishing the right questions at the planning stage. Rather than directly visualizing brand messages, we define the emotional state in which viewers are meant to remain within the space. Together with brand partners, we clarify priorities and experiential direction so that later design and technical decisions remain consistent. The second key consideration is the relationship between space and screen. In large scale installations, the viewer’s movement, sightlines, and duration of stay shape the experience more than the image itself. We treat the screen as part of the spatial environment, designing rhythms and loops that function naturally for both passersby and those who linger. The final consideration is operational sustainability.

Media art installations change dramatically depending on time of day, ambient light, season, and crowd density. By anticipating these variables, we adjust color, contrast, speed, and sound intensity to ensure stability over time. The central question we always return to is whether media art remains merely a device that explains a brand or becomes a sensory environment in which the brand resides. When this criterion is clear, consistency across planning, installation, and operation naturally follows.

Within a rapidly evolving technological environment, which technological trends or media formats is CUZ currently most attentive to, and what kinds of experimentation are you interested in pursuing?

CUZ focuses less on technology itself and more on the changes in state that technology produces. At present, we are particularly interested in real time responsive media and multimodal media combined with wellness. Structures that allow content to shift subtly in response to a viewer’s movement, gaze, or duration of stay transform viewing into a form of co presence. Additionally, content that synchronizes vision, sound, rhythm, and spatial perception to regulate emotional and physical states will become increasingly important. All of these developments matter because they align with the idea of designing experience. Media is no longer merely a vehicle for delivering messages, but an environment capable of altering human states.

Finally, what advice would you like to offer to younger creatives who aspire to work in media art, video, motion graphics, or interactive design?

I would advise them not to begin with technology. Tools change far too quickly. Instead, it is more important to ask why a particular scene needs to exist. Especially for those interested in brand collaborations or large scale installations, the priority should not be personal expression, but the state people are meant to experience within a space. Media art is not about creating something that simply looks impressive. It is a form of responsible sensory design. I believe that understanding this point is what allows one to sustain a long and meaningful practice in this field.