< Photo by Zulfugar Karimov on Unsplash >

As artificial intelligence deeply enters the realm of design, we find ourselves naturally conversing with AI even for the smallest curiosities, rather than typing keywords into a search bar. This reveals how reliant we’ve become on AI in our everyday lives. It's no longer just about finding answers—our thought process itself is becoming shortened, and we’re increasingly accustomed to accepting results uncritically. While AI may seem like an all-powerful tool, it simultaneously poses the heaviest question: that of ethical responsibility. Design is no longer merely an act of drawing. It is now a process of generation, acceptance, and sometimes rejection. If a product designed by AI causes errors or reinforces societal biases, who is responsible? Is it the algorithm? Or the designer who provided the data and approved the final output? We are already entrusting far more decisions to AI than we realize.

Unconscious Bias

The first ethical issue raised by AI in design is unconscious bias. AI can only think based on the data it has learned from, and so it reproduces the prejudices and inequalities embedded in that data. Therefore, the "optimal answer" provided by AI may actually be a biased one. For example, when describing a grandmother cooking Korean traditional food, AI generates a relatively accurate image. But when simply prompted with "a grandmother cooking traditional food in the kitchen," the result is more likely to reflect a Western kitchen. This is due to the data AI was trained on being skewed towards specific cultures.

<Generated by Midjourney (Prompt): Left - a grandmother in the kitchen cooking traditional food / Right - a Korean grandmother wearing traditional hanbok, cooking kimchi in a Korean-style kitchen>

This also applies to product design. When asked to generate a design for a portable speaker, AI repeatedly presents shapes resembling the well-known B&O brand. This bias extends beyond images. In mobility design, for instance, AI may optimize seat structures and airbag positions based on the physical attributes or driving patterns of typical users. However, if the data lacks representation of certain races, genders, or non-standard users like pregnant women, these "optimized" designs may only ensure safety and comfort for some users while posing inconvenience or even danger to others. This issue is also evident in facial recognition services and fashion design.

<Generated by Midjourney (Prompt): A woman on the cover of a high-fashion magazine>

When AI is trained on specific races or body types, other groups are excluded, leading to distorted standards spreading throughout society. Such bias doesn’t stop at aesthetics—it can reinforce social inequalities or exclude the voices of certain groups. If cultural diversity is not adequately represented, the world risks being confined to a singular aesthetic and biased standards. Designers must look beyond the form suggested by AI to uncover hidden ethical blind spots. In other words, the designer must play the role of seeing the unseen.

< Generated by Midjourney(Prompt) : A woman on the cover of a high-fashion magazine >

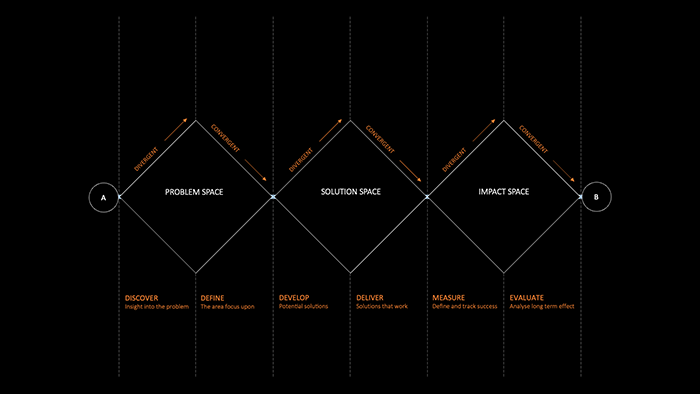

Blurred Authorship and Shifting Responsibility

AI blurs the boundaries of authorship and responsibility. According to a 2024 Figma report, 59% of designers already use AI in their workflows. However, only 32% said they fully trust the AI’s results. This implies that most designers still have to modify or verify what AI produces.

< Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash>

This shift shows that responsibility is moving from the creator to the manager. If a design made by AI fails in the market or causes ethical issues, the designer who approved and released it cannot avoid responsibility. As the line of responsibility becomes more complex, ethics becomes an even more urgent issue. The question now becomes: where should ethics be placed in the design process? Designers are not just creators—they are also the ones who choose and approve, bearing the ethical risks involved. They must consider the ripple effects of design outcomes on society, and establish themselves not only as technical verifiers but also as ethical ones.

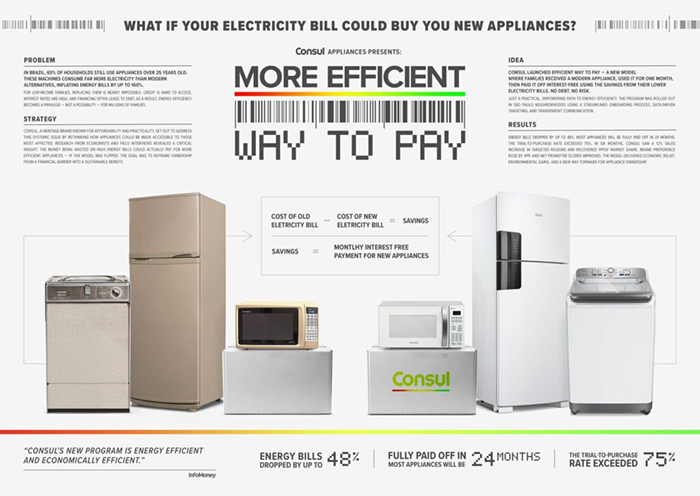

The Reason Designers Exist

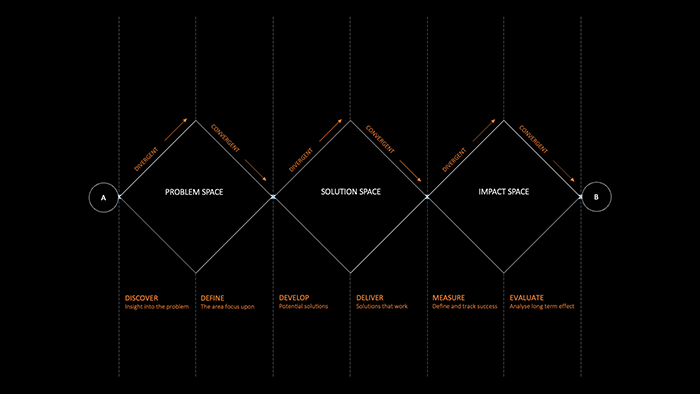

<Evolving Double Diamond Design Process: Impact Space>

The added stages of "measurement" and "evaluation" in the Double Diamond process act as safeguards for ethical responsibility. Designers must continue to track and analyze the long-term societal impact of their designs even after product launch. When the efficiency of AI collides with human ethical values, designers must have the courage to choose the latter. Ultimately, AI cannot be held accountable. It is merely a tool without moral judgment. Designers must take on the managerial role, which means securing ethical leadership. Therefore, design education in the AI era must go beyond teaching prompt engineering. It must cultivate critical AI literacy. Furthermore, design education must require not only technical proficiency but also social imagination and moral reflection.

Designers go beyond being creators; they become mediators of societal values and culture. Future designers must not be passively dragged by the flow of technology—they must propose directions and lead social consensus. Their decisions influence not only the quality of a product but also lifestyles and societal value systems. Designers with ethical leadership are not just creators, but architects of the era’s transformation. They must also take on roles as coordinators and critics amid changes in politics, economy, and culture—this is how design becomes a tool for social agreement.

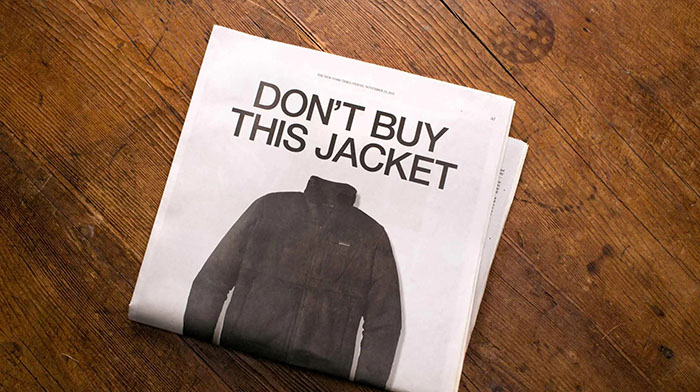

AI has opened the door to infinite creativity, but it has also drawn the most complex and weighty ethical boundary in design history. The choice, in the end, is ours. In a world full of AI-made decisions, the most human act a designer can perform is deciding what not to design. The designer of the future must be more than an artist who creates beautiful forms—they must be ethical strategists designing a fair and responsible society. This is the moment when design becomes not just an output, but a social promise.