Director Eitaro Satake Architect at teamSTAR

"Director Eitaro Satake, architect at teamSTAR and winner of ADP’s Design of the Year, pursues structures that echo nature and forms that endure. His award winning Villa A breathes with its site through a vaulted roof of continuous CLT arches that recall white waves, emerald flooring that suggests a shallow sea, and a shell like floating stair—gestures that soften the line between inside and out and reinterpret the Japanese idea that house and garden are one. Satake’s philosophy begins with harmony and reverence for nature and aims for future classics, honoring simplicity, purity, the beauty of imperfection, and the value of suggestion while uniting traditional craft with precise structural logic. Extending from resorts to memorial architecture and the revitalization of shrines and temples, his practice argues for the social role of design and resonates with ADP’s vision of Legacy Beyond Asia. This interview records how he composes a living interface where architecture and nature meet as one continuous experience."

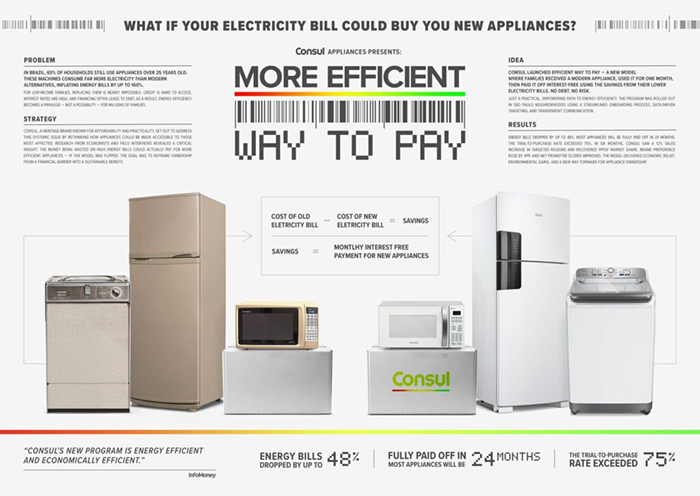

To begin, could you briefly introduce yourself and share the story behind your award-winning project Design of the Year? We would love to hear about the intentions behind the vaulted roof of continuous CLT arches, the emerald green flooring evoking the shallow sea, and the shell-like floating staircase.

My name is Eitaro Satake. It is an unexpected and tremendous honor to receive the Design of the Year at the prestigious Asia Design Prize. Our team, teamSTAR, works under the concept of “Making the world beautiful through the power of design.” We specialize in hospitality design for resort hotels, ryokans, and private villas. Drawing on our experience in resort facilities, we also design columbaria and funeral facilities, and we are involved in the revitalization of shrines and temples. Our design philosophy is to create what we call “future classics.” The award-winning project, Villa A, embodies this vision through three key elements: Vaulted roof of continuous CLT arches Inspired by the overwhelming expanse of the ocean visible from the site, we sought a sculptural design in harmony with its stunning natural surroundings. The continuous wooden arches of the CLT roof resemble white ocean waves. To realize this, we referred to traditional Japanese bridge engineering and construction methods. Emerald green flooring evoking the shallow sea To express the concept of “living with the sea,” we adopted a color scheme that evokes yachts and the ocean. The living room floor captures the image of a shallow sea, creating a sensation of relaxing above water. Shell-like floating staircase The underground entrance hall was conceived as an undersea realm. The white, spiral staircase resembles a seashell, appearing to float in water. In fact, the concrete staircase does not touch the floor.

< Villa A, Design of the Year 2025 >

This project blurs the boundary between indoors and outdoors with elements such as the expansive curved roof and the large sash window that opens the interior to the exterior. How do these design gestures relate to Japanese notions of space and nature?

In Japan, there is a phrase “teiokkuichinyo,” meaning “the garden and the house are inseparably one.” It expresses the Japanese appreciation for living in harmony with nature and experiencing the changing seasons. Our design, which allows the indoors and outdoors to flow seamlessly and makes one forget they are inside, reflects this traditional spatial and natural sensibility. Japanese architecture has long emphasized the ambiguity between inside and outside and harmony with nature.

In your work, how are these traditional aesthetics being reinterpreted and translated into contemporary forms?

The sweeping roof spanning the site, floors that follow the sloping terrain, organic forms inspired by the sea and yachts, and details that create continuity through identical materials indoors and out—all of these design elements evoke nature. This contemporary and sculptural architecture is derived from the traditional Japanese aesthetic that cherishes ambiguity between inside and outside and harmony with the natural world. In our approach, we set out to compose a precise harmony between architecture and nature, so that neither reads as a backdrop to the other. As a result, the two realms do not stand apart but operate as a single living interface—continuous, perceptual, and felt in everyday use.

< TOUTOKI >

From your perspective, what distinguishes Asian design approaches from Western traditions? How do you see your winning project reflecting or expressing an Asian design identity?

Asian, especially Japanese, design is characterized by an aesthetic of “simplicity and purity” and by a reverence for “the beauty of imperfection.” Rooted in Taoist and Zen philosophies, it values harmony with nature, a sense of impermanence, and the “value of suggestion,” which stimulates the viewer’s imagination by avoiding symmetrical forms. Rather than following trends, it respects individual inner spirituality and pursues beauty in the present moment. In contrast, Western design, shaped by monotheistic traditions, often regards design as an expression of ideology and views nature as something to be overcome. Asia, and Japan in particular, is rooted in polytheism, where gods and Buddhas coexist and dwell within nature. This underpins a design identity that venerates nature and values unity with it. Villa A reflects this Japanese identity through its many maritime and yacht-inspired motifs, the roof aligned not with the sea but 45 degrees toward Mt. Fuji, and its organic, asymmetrical forms.

< Prabha >

The Asia Design Prize carries the slogan “Legacy Beyond Asia.” What does “Asian design legacy” mean to you, and how is it embodied in your architectural practice?

Our goal is to create architecture that becomes a “future classic.” For me, the essence of Asian—particularly Japanese—design heritage lies in harmony with and reverence for nature. Traditional resort architecture and historic temples exemplify this. This is why we not only design resort hotels but also work on the revitalization of shrines and temples. For example, alongside Villa A, our ossuary hall project, "Prabha"-an hotel-like ossuary—which also won the ADP Grand Prize in 2025—embodies this heritage. Conceived as “a room for the departed,” it offers a space filled with tranquility and light for both the deceased and their families. The “Garden of Silence,” a dry landscape garden for quiet remembrance, is a key feature. By integrating nature into design and bringing Japan’s timeless beauty into contemporary lifestyles, we strive to embody the “future classic” in our architectural practice.

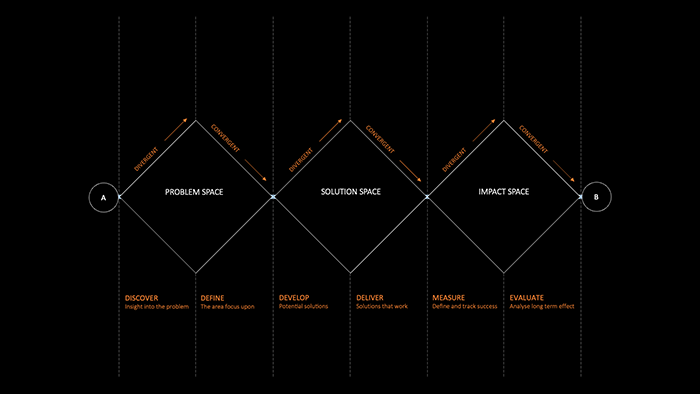

This project required both advanced technology and extremely precise construction techniques. In achieving both structural logic and formal beauty, what principles or values guide your design process?

“Good design resembles nature.” This phrase is one of our design policies. The beauty of nature inherently contains structural rationality. Seeking aesthetic beauty naturally leads to structural rationality. Achieving the kind of natural beauty we aim for often requires advanced structural analysis, even when the design appears simple. Traditional construction methods often hold the key to solving these challenges. For example, in realizing the timber CLT roof, we studied the structures and techniques of famous wooden bridges, such as the "Kintai Bridge". To create a “future classic,” we learn from the classics. We incorporate nature both physically and structurally into the spaces we design.

< STAR Lounge >

Looking ahead, what do you see as the most pressing challenges for architecture and design in Asia today? (e.g. climate crisis, urban density, sustainability, or digital technologies)

It is difficult to summarize the challenges in a single phrase because they differ by region. In Japan, issues such as an aging population, declining birthrate, and urban crowding are critical, whereas in countries like Vietnam, population growth, rising incomes, and rapid economic development pose different challenges. From a global perspective, in a world where wars erupt over religious conflicts and territorial disputes, a peaceful Asia that tolerates diverse values and enables coexistence is expected to become the world’s center. Architecture and design have a mission to help drive that vision. Designers must recognize that design is not merely about surface form—it has the profound power to solve business and social problems. Design is power.

< Prabha >

For stronger pan-Asian solidarity, what kind of collaboration or exchanges do you think designers should pursue across regions such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and Southeast Asia?

For the reasons above, pan Asian solidarity is essential. Designers from each country should bring specific challenges to the table and address them together through dialogue and joint work. Practical steps include cross region studios and residencies, rotating teams through partner cities, and shared briefs on aging, climate, mobility, and inclusive public services. We should build an open library of research, materials, and case studies in multiple languages, hold peer review clinics online and on site, and run travel programs that pair studios with local craftspeople, manufacturers, and civic groups. Joint exhibitions and pilot projects ought to carry clear measures of success, such as repair uptake, energy use, or accessibility adoption, so that learning can travel with the work. A modest fund and a mentorship network to support student and early career exchanges would complete the loop. Design is power, and how we direct it matters. Just as important, we must keep a steady optimism, the belief that the future can be made better when we work together.

Finally, as the recipient of ADP’s highest honor, what future vision or architectural challenges would you most like to pursue in the coming years?

I would highlight three key directions I’m eager to explore: 1. Finding New Value in the Old I want to keep practicing spatial design and craftsmanship that discover new value in things from the past. At STAR LOUNGE, we experimented with creating spaces using antiques and raw materials, and from that experience we launched an up-cycling brand called “TOUTOKI” which literally means “questioning time.” The name captures our philosophy of seeing timeless worth in old objects. Working with antique dealers, iron artisans, and other professionals, we aim to create spaces and objects that give new life to reclaimed materials and vintage tools. 2. Temples Where Tourism and Spiritual Experience Coexist Here in Japan we are developing a project to create temples where visitors can actually stay overnight—places where travelers can experience everyday life and spiritual practice together. I would love to bring this idea of “living life as a journey in a stayable temple” to other parts of Asia. 3. Healing Grief Through the Power of Design I also hope to realize projects for columbaria, funeral halls, and crematoria in Taiwan, Korea, China, and Southeast Asia. These projects are about using design to help heal the sorrow of loss. Just as resort hotels and private villas can soothe the living, I believe design can comfort those who have passed and their families. Design has the power to heal. By believing in that power and working hand in hand with designers and architects across Asia, I believe we can take one step closer to creating architecture that will truly become “future classics.”

editor@asiadesignprize.com