When we talk about design, the words that most often come to mind are “beautiful” or “stylish.” Yet in industrial design, form is never just a matter of aesthetic taste. It is the outcome of countless constraints, judgments, and compromises—a visible record of complex reasoning. Form, in this sense, is not simply what the eye perceives; it is what remains after a designer has analyzed and resolved a problem through logic and choice. Even so, we still tend to consume design purely as a visual language. In an age where AI can generate thousands of images in seconds, “beautiful” is no longer a rare emotion. The more crucial question now is “Why does it look this way?” To view design without understanding the reason behind its form is to see only half of it. Especially for emerging designers who have grown up in the digital era, the true skill lies not in appreciating the surface of form, but in reading the structural logic beneath it.

In industrial design, form is always a negotiation. To draw a single line, a designer must consider countless variables: material properties, ergonomic comfort, production efficiency, brand identity, and even the subconscious feelings of the user. Design serves people, yet its process unfolds across deeply layered complexities. What appears as a simple contour or curve is, in fact, the condensed result of these collisions and harmonies between constraint and creativity.

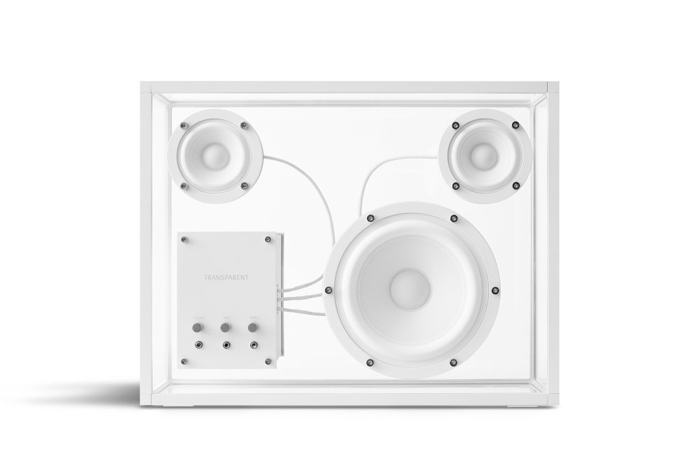

< Image Credit: Transparent Speaker >

To truly understand form, we must look beyond aesthetics and trace the logic that produced it—like reading an X-ray to reveal the hidden structure beneath. When analyzing form, designers often think in three overlapping layers.

< Image Credit: Polestar >

The first layer is functional logic. Every form exists to solve a specific problem. For instance, the reason a car’s taillight extends toward its side is not purely stylistic. It improves side visibility for safety and adjusts airflow to enhance fuel efficiency. Every curve and angle serves a purpose. While AI can calculate efficiency, it cannot yet comprehend how that efficiency translates into human sensory experience. The designer’s task is to bridge that gap—to align performance with feeling.

< Image Credit: Apple >

The second layer is the logic of production and materials. Design exists within reality’s constraints. No matter how elegant a concept may appear, if it cannot be fabricated, it has failed. The reason many products have rounded corners is not only an aesthetic preference but often a result of mold durability, injection efficiency, or assembly precision. Surface texture, thickness, and radius are all determined by manufacturing technology and cost structure. Beauty operates within the limits of technology. A designer’s creativity must therefore flourish inside these boundaries—not by forcing the impossible, but by finding the most convincing solution within what is possible.

< Image Credit: Bang & Olufsen >

The third layer is the logic of brand and user. Design is a language that visualizes identity and anticipates emotion. The consistency of a brand’s form is not merely stylistic—it communicates its values. A brand that favors sharp geometry projects strength and trust; one that embraces soft curves conveys empathy and inclusiveness. Form becomes a nonverbal contract between brand and user, and the designer is its linguist, constructing a grammar of visual promises. It is at the intersection of these three logics—function, production, and brand—that form becomes persuasive. And at the center of that persuasion lies one enduring question: why. AI can calculate form, but it cannot explain what that form means. Its outputs may appear flawless, but they lack human context. The true value of design emerges in this act of interpretation, where logic meets empathy. Many students studying design rely heavily on platforms like Behance or Pinterest, replicating others’ work as visual reference. Yet in doing so, they often neglect the reasoning that gives form its meaning, leaving them unable to explain their own creations. To them, I often say: “Do not look only at the form—look at the reason behind it.”

Anyone can create a beautiful shape, but few can clearly articulate why it was made that way. Interpreting form means not only analyzing function but understanding how it connects to emotion, culture, and ethics. Design is both a visual and social language. Curves suggest warmth, edges suggest decisiveness, balance conveys trust. The logic justifies form, but emotion makes it loved. Design finds its power where these two worlds—reason and feeling—exist in harmony. AI may produce efficient forms built on vast data, but only humans can imbue those forms with emotion and story. The designer’s role is to translate logic into feeling, to give structure a soul. To ask “why” rather than “is it beautiful” is not just an analytical habit—it is a way of thinking. The ability to interpret form is not only a technical skill but a worldview. Those who can read the traces of decision within form can grasp the essence of things themselves. Developing the eye for design is therefore an act of expanding the depth of thought. Design’s essence lies not in its results, but in its process. Form is not the endpoint of thought, but its record. When designers interpret the world through form, and the world in turn sees itself through design, design transcends decoration—it becomes philosophy.

AI can calculate form. But the reasons, the emotions, and the humanity within it remain in the designer’s hands. To read form is to read humanity itself. The moment we move beyond saying “beautiful” to asking “why,” design ceases to be an image and becomes a language. And for now, only human designers can speak it.