AI is fundamentally reshaping the way architecture and design are produced. With just a few lines of text, the form and atmosphere of a building can be generated, and on global platforms, the “Zaha Hadid” style has become one of the most frequently searched architectural keywords. In a climate where architecture is increasingly consumed as imagery, we are prompted to ask once again.

In the age of AI, what kind of creative architectural design should Asia pursue?

Zaha Hadid Architects already employs generative AI actively in the early design stages, exploring hundreds of alternatives within a short time. AI expands conceptual thinking, enhances design efficiency, and has become firmly embedded in the creative workflow. However, the speed of generation cannot replace the essence of architecture. Creativity in architecture ultimately emerges from accumulated understanding, and from the slow, reflective processes of interpretation and inquiry.

< Image source: The studio is also working with Stable Diffusion >

The recent trend of AI-generated “Ghibli-style” images reveals this limitation starkly. Although the colors and compositions seemed similar, they failed to capture the worldview, emotional tone, and craftsmanship that Studio Ghibli has cultivated over decades, and the trend faded as quickly as it appeared. AI may visually imitate Zaha Hadid’s fluid curves, but it cannot replicate the questions those forms pose within the contexts of city, structure, and material. In other words, while appearance can be replicated, the creation of architectural language is impossible without long-term human inquiry. Moreover, the discourse surrounding AI unfolds differently across regions, raising particularly fundamental questions in Asia.

While Western contexts often frame AI-related concerns around copyright and ethics, Asia is more troubled by the erosion of place, materiality, memory, and communal context. Asian architecture has developed through its relationships with nature, climate, terrain, materials, and people—depths that cannot be replaced by computation alone. The examples of architects who transformed the architectural language make this clear. Shigeru Ban elevated paper tubes into structural materials, proposing a new direction for disaster-relief architecture. Frei Otto pioneered lightweight tensile structures that create maximum spatial volume with minimal material. Liu Jiakun reinterpreted earthquake debris into recycled brick, embedding collective scars and memory into the architectural fabric. Their innovations did not emerge from flamboyant forms but from sustained exploration and reimagining of materials and place.

< Image source: Frei Otto >

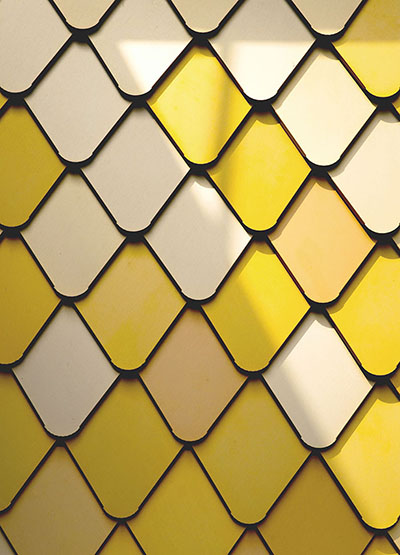

My own research aligns with this perspective. “The Perpetual Golden Leaf,” an exterior material developed by translating the temporality of fallen leaves and sunsets in Ulsan into architectural surface, was an attempt to encapsulate the fleeting qualities of nature and the landscape of an industrial city within a single panel. This was not merely the development of a finish material, but a design experiment aimed at transforming urban memory and regional identity into material expression.

< Image source: ‘The Perpetual Golden Leaf’ exterior material >

This is a process AI cannot replace. AI may generate convincing images of paper tubes, tensile structures, recycled brick, or golden-leaf panels, but it cannot reproduce the reasons these materials emerged, the time embedded within them, or the traces of repeated failures and experiments. The act of imbuing materials with meaning and creating new architectural language originates in deep human thought and discernment. Yet this does not imply that AI should be resisted. AI is not a technology that suppresses creativity, but one that expands its potential. The central question is whether we regard AI as a mere “image generator” or as a platform for exploring new combinations and possibilities. The breadth of exploration that AI enables enriches the tools and materials available to architects, and when combined with human interpretation and experience, it becomes the basis for new architectural expression.

In the age of AI, the creative architectural direction Asia must safeguard is not the rapidly consumed image but the authenticity of process; not the automation of technique but the interpretation of people, nature, and culture; not mimicry but a commitment to establishing one’s own architectural language. When the vast possibilities offered by AI are layered with the architect’s thoughtful inquiry and accumulated understanding, Asian architecture can finally realize a truly creative architectural paradigm suited for the AI era.