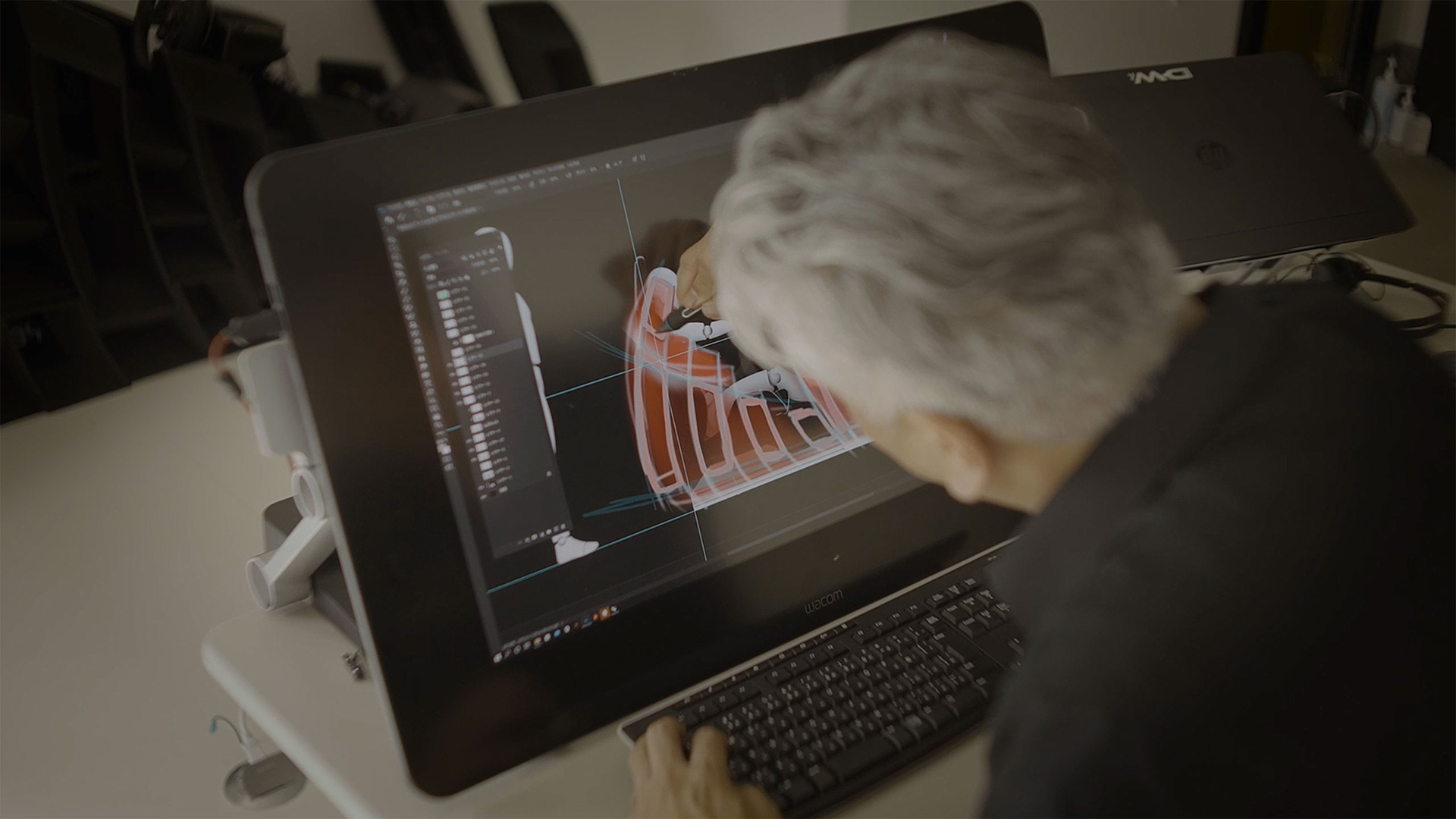

I am Kenichi Mizuno, the CEO and designer of D-WEBER Co., Ltd., a personal design office. It has been 23 years since I founded the company. Initially, I mainly worked on graphic design projects, but as I began to publish mechanical 3D works as self-initiated projects, requests for product design gradually increased, leading to the work I do today. My commercial design, which is uniquely developed through experience in both 2D and 3D design, has been highly regarded and has allowed me to participate in design development projects, particularly with automobile manufacturers. In addition to my main work, I also serve as the Chubu Regional Director of the Japan Industrial Designers’ Association (JIDA), the only industrial design organization in Japan. Through this role, I am actively engaged in promoting the value and usefulness of design and designers.

What is the most memorable achievement or experience in your design career that you believe would be most compelling to readers?

One of the most memorable and remarkable experiences in my career was winning both the Grand Prize and the Gold Prize at the ASIA DESIGN PRIZE 2021. Honestly, I never imagined achieving a double crown as an individual, so when I first saw the results, I couldn’t help but repeatedly wonder, “Is this some kind of mistake?” At that time, the world was clouded with fear and uncertainty due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Amid such a dark atmosphere, the news of this award became a ray of hope—not just for me, but also for the people who worked with me and for my local community. These award-winning pieces were created in collaboration with small local factories, which had been severely impacted by the pandemic. The recognition was not just a personal triumph, but a shared victory that brought light to everyone involved.

What was the story behind those award-winning works, and how did the collaboration with local factories come about?

It all began when I happened to participate in an event organized by the local government where I live. There, I met the owners of nearby small factories for the first time. Until then, I had very little interaction with local businesses, so this encounter marked a significant turning point in feeling more connected to my community. Since it was the first time we were working together—and amidst the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic—our possibilities were limited. Communication across different industries was also challenging, and understanding each other didn’t come easily. We fell into a cycle where time passed but progress didn’t. Eventually, I reached a breaking point and felt that “if I give up here, everything we've done so far will be wasted.” That feeling exploded inside me.

I stopped holding back and laid everything out, channeling that energy into reigniting our motivation in a world clouded with uncertainty. After that breakthrough, we were able to bring the two projects to life—and those became the very works that earned both the Grand Prize and the Gold Prize.

What kind of impact did those award-winning works have after their release?

The moment these works were unveiled, they quickly spread through online news and social media, creating a huge buzz. The first exhibition offer came from “Tsutaya Electrics +” in Futako-Tamagawa, followed by a display at the Yurakucho location of “b8ta,” a Silicon Valley–born retail concept. I will never forget the overwhelming joy of having my designs recognized by people around the world who are familiar with outstanding creations. Locally, people reacted with surprise—“We have a designer like this in our town?!”—and the two works were even selected for the city's commemorative postage stamps, for which I was also entrusted with designing the overall layout. This opened the door to deeper collaboration with my local community.

Having moved to this city from another nearly 20 years ago, with little prior involvement in local affairs, this was a major transformation for me. Furthermore, this story led to my being selected as a speaker for “TEDxAnjo2022,” giving me the chance to share my philosophy as a designer with the world. I’ve always had a personality that doesn’t allow for giving up, which at times made life difficult. But now, I’ve come to accept that “I’m someone who never gives up.” I strongly believe that innovation is something we must take the initiative to create ourselves.

Could you tell us about your creative process? If you have a personal design approach, we’d love to hear about it.

I don’t place much importance on a fixed creative process. Every time I receive a commission, I feel both joy and pressure. Even though I’m called a designer, ideas don’t spring forth endlessly, and since I work alone as a creator, I must complete the work within the limits of my own capabilities. This isn’t the most ideal situation from a business perspective, but that’s just how it is. So rather than trying to avoid running out of ideas, I simply follow my curiosity. I constantly expose myself to a variety of information and never miss the daily news. I also make time for short trips or drives, where I let my mind wander while taking in the scenery. The air I once felt years ago, the meal I had recently, or the sights I encountered while walking abroad—all of these experiences accumulate like drawers in my mind. And then one day, a source of inspiration emerges from those drawers of experiences and sensations.

Could you tell us about your creative process? If you have a personal design approach, we’d love to hear about it.

I don’t place much importance on a formal creative process. Every time I receive a request, I feel both joy and pressure. As a solo creator, ideas don’t come endlessly, and I have to work within my own capabilities. It may not be ideal from a business perspective, but that’s just how it is. I’m always gathering information out of genuine curiosity, not necessarily to prevent creative blocks. I check the news daily, take short trips, and let my thoughts drift while driving and observing landscapes. Experiences like the air I once felt, a recent meal, or scenery I discovered while traveling all accumulate like drawers in my mind. Then, when the time comes, those drawers open and inspiration emerges.

I also love talking with people and frequently communicate with others. I especially enjoy laughing over unique topics—it might come from a strong desire to bring joy to others. That’s not just about service; I simply feel happy when the person in front of me smiles or is surprised. So when I take on a project, even if it’s difficult, my desire to impress and delight is stronger than my hesitation. Even when ideas don’t come easily, there’s always that moment when, under pressure, my hand spontaneously begins to sketch—and a simple draft becomes a breakthrough. From that moment, I accelerate and bring the idea to life. That’s my routine. No matter how much I research or plan, good ideas don’t always come from that. I focus more on results than the process. Since I believe there’s no single correct method, if I had to describe my process, it would be: “Let the result speak, not the steps.” Perhaps that’s why people often call me a craftsman type.

Who is the designer you respect most, and how have they influenced you?

This is a common question, but honestly, I hardly know any designers by name or face. I had difficulty socializing from a young age and poured my passion into drawing or playing with clay. It became a vital part of my life—something I needed to survive. So I didn’t become a designer out of admiration for anyone, and I never formally studied design. Even now, I often meet famous designers without knowing their names or achievements, which can be embarrassing. I’m also not interested in art exhibitions or museums, so I rarely recognize people in the field.

People who’ve influenced me are only those I’ve interacted with personally. When it comes to design, I don’t follow specific people—I simply adopt anything I feel is good based on my own standards. If I had to name an influence, it would be the anime and manga I loved as a child—like Gundam or Dr. Slump. They were filled with dreams. Akira Toriyama’s beautiful illustrations and groundbreaking gag stories especially struck me. I think it was around then that I first began wanting to be recognized for my own creations.

How do you think the design market will change in the next 10 years? What are you doing to prepare for it?

In the past decade, the rise of social media has increased the power of design as a communication tool—but at the same time, it’s diminished its perceived value. For freelancers, the spread of side businesses has brought new opportunities, but also intense price competition and quality concerns. It’s become harder for independent designers to survive. On the other hand, this shift has created chances previously unthinkable. With enough skill and funding, it’s now easier to break into new businesses. Design is essential for any venture, but the ambiguity around appropriate pricing due to SNS culture means independent and in-house designers now have to offer more than just design to stay afloat. The pressure to go beyond design is rising.

In my view, 10 years from now, we will likely face threats even more disruptive than generative AI. If that happens, design itself will become increasingly unique in nature. This might not be ideal for us designers, as it could become possible for anyone to simply express their preferred words or images and instantly generate what they want—a world of AI-driven haute couture. When that time comes, how will the value of design evolve? I believe the answer lies in “texture” or “tactility.” The emotional quality of something created by human hands—its subtle imperfections and warmth—may become a central appeal for a new generation of consumers. People might crave that human touch more than ever.

As Japan faces a declining birthrate and aging population, with wealth concentrating among people in their 60s, designs tailored to specific age groups will gain importance, and those users will be willing to pay for them. Historically, society has always sought novelty, but in an era where AI can easily generate “newness,” our very definition of it will likely shift. While I can’t say I’m fully prepared, I believe it’s vital to trust in myself, constantly pursue what I find interesting, and never neglect personal growth. With a mindset of flexibility and a commitment to evolving alongside the times, I intend to keep growing and embracing change.

Do you have a personal design philosophy or belief? And what is your vision for the future?

My foundation in design comes from using it as a "means of survival." My core belief is not about being good at everything, but rather about having one unshakable strength that no one can beat. Some people approach design academically, and I don’t deny that—on the contrary, I respect it as another valid way to live. But personally, I see design as a skill given equally to everyone, though one that inherently invites clear distinctions in quality. It took me 30 years before I could confidently say, "I am a designer." Since then, design has become fun for me. I feel that this moment—right now—is the most enjoyable point in my life. I’ve spent my life designing myself to feel that way, and I think it’s finally paying off.

As for the future? I simply want to enjoy it even more. I’ve come to understand that the more I enjoy what I do, the more results I can achieve. Two years ago, I renovated my studio and launched a design consultation service. It has since become a place for local business owners and, at times, students to gather and exchange ideas. I'm excited about the possibilities of co-creating something new together someday, as we continue making design feel more familiar and accessible to everyone.