Design is about asking questions. And today, the questions we must ask have only grown large

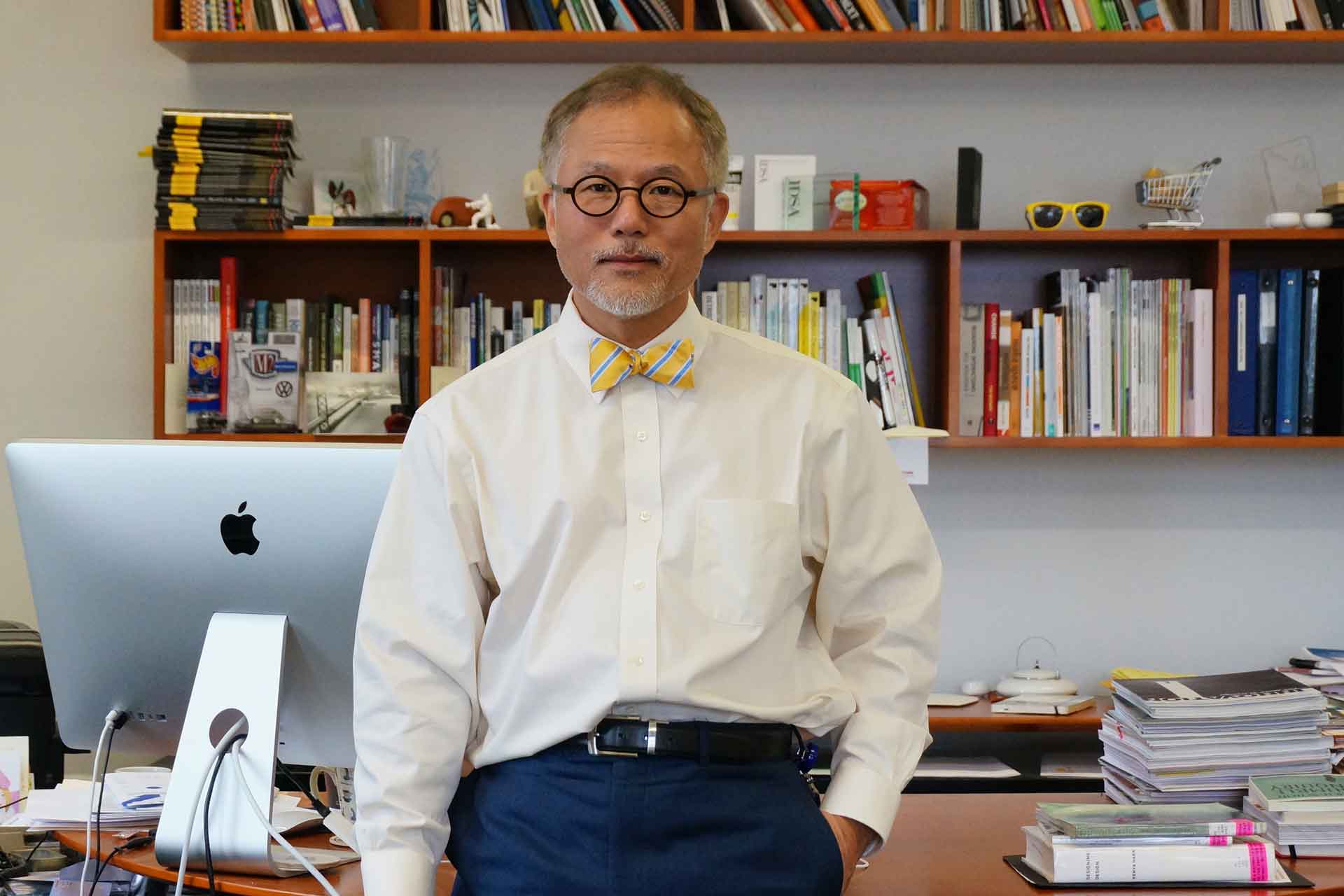

Prof. Sooshin Choi Artistic Director of the 2025 Gwangju Design Biennale

“Design is about asking questions. And today, the questions we must ask have only grown larger.”

South Korea is rapidly emerging as a visible force on the global design stage. Yet when asked what defines Korean design, we often struggle to answer. The challenge is to move from fast followers without a clear identity to leaders who set new agendas. Professor Sooshin Choi, Artistic Director of the 2025 Gwangju Design Biennale, offers a compelling response: we must shift from passively solving problems to actively asking the right questions and pursuing our own answers. Professor Choi is both a renowned educator, with experience at SCAD (Savannah College of Art and Design) and other leading institutions, and a seasoned practitioner in industrial and automotive design. As curator of the upcoming Biennale, his vision centers on a powerful theme: “YOU, THE WORLD: How Design Embraces Humanity.” This conversation looks beyond exhibition curation; it is a statement that seeks to remap Asian design discourse and to locate identity, humanity, and future direction through the lens of design.

Why do you believe a pan-Asian design platform like the Asia Design Prize (ADP) is needed now, especially from your perspective as someone who has worked across both the U.S. and Korea in design education and industry?

For a long time, the field of design has been shaped by Western centric aesthetics and industrial logic. Today, as economic, cultural, and technological centers continue to shift toward Asia, design must be reinterpreted and reconstructed through this lens. Asia is not a single voice; it is a vast and diverse collective of sensibilities shaped by millennia of cultural heritage. That richness calls for a platform that can both represent and transmit these organically emerging design languages, attitudes, and philosophies to the world.

In my view, ADP should go far beyond being an award that simply celebrates winning entries. It should grow into a central platform that uncovers and spotlights Asia’s unique worldview in design, and it should function as a true forum for dialogue. A platform is not merely a stage for display. Much like a train platform, it is a place where people gather, exchange directions, and set off on different journeys. It should be a structured space for questions and responses, a site for design discourse that points the way forward. Most importantly, we must approach the idea of pan Asia not as a push for uniformity, but as a respectful framework for cultural diversity. Korea, China, Japan, and Southeast Asia each hold distinct aesthetic values and social codes. The challenge, and the opportunity, is to harmonize these voices into a shared design language that can engage the world. Without this, pan Asian risks becoming a mere regional subsection within a global hierarchy.

ADP should not stop at comparing differences. It should explore how resonance and synthesis can emerge from within those differences. In that sense, I see ADP less as a place for judging final outcomes and more as an experimental lab that shares questions and tests how design can propose new directions in response. Only then can we uncover the identity and possibility embedded in the idea of Asian design. There is no better time than now. ADP is well positioned to lead this exploration from the center of an evolving conversation.

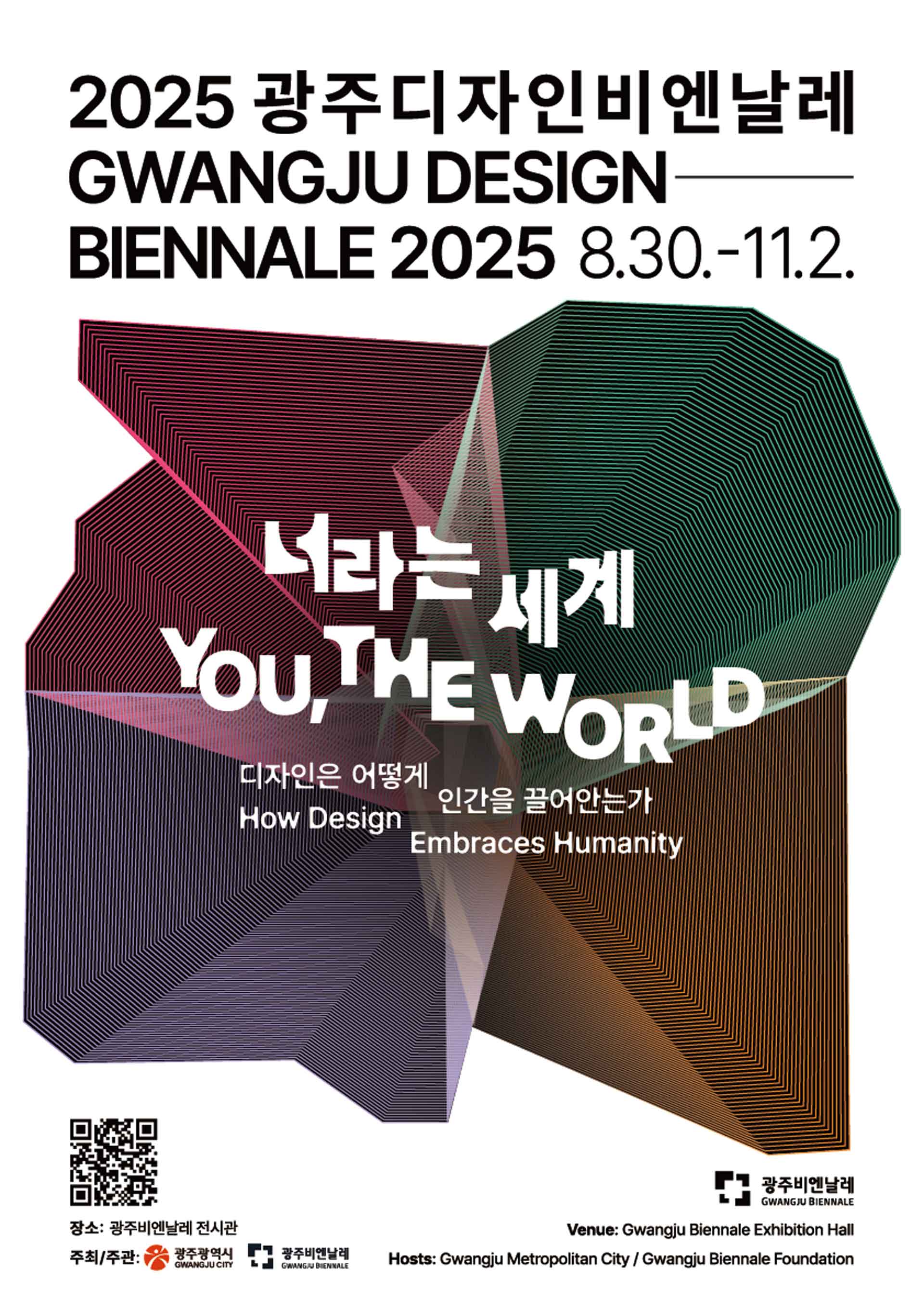

The theme of the 2025 Gwangju Design Biennale is “YOU, THE WORLD: How Design Embraces Humanity.”

What design or sociocultural considerations informed this theme, and how do you see it connecting to the future direction of Asian design?

This year’s theme, “YOU, THE WORLD: How Design Embraces Humanity,” is not poetic rhetoric or a sentimental title. It answers the most urgent question of our time: What is the essential role of design in a world that needs healing, connection, and mutual understanding? My intention was to position inclusive design not as a passive or purely moral idea but as a strategic and future oriented framework that redefines design as a language of connection between individuals and communities, between markets and policies, and between culture and technology. For too long, design has been treated as a tool for industrial success, valued for efficiency, profitability, and trend responsiveness. In that climate, human centered values have often been overshadowed by market centered performance. While educators such as Victor Papanek consistently advocated for social responsibility in design, inclusion has too often remained peripheral, regarded as ethical but not essential in both corporate and academic settings. Through this Biennale, I hope to challenge that perception. Inclusive design is not charity, and it is not a gesture of the strong toward the weak. At its core, it is a design strategy for all lives, one that embraces diversity across age, gender, ability, nationality, and access to information.

If design can operate as a system that acknowledges differences and integrates them into shared experiences, it becomes more than a creative industry; it becomes a driving force for social cohesion and progress. Western interpretations of universal or inclusive design have often emphasized accessibility and usability, viewing design primarily through the lens of the individual. By contrast, Korea and many Asian cultures place deep value on the collective, on the idea of “us.” This makes Asia fertile ground for expanding the meaning of inclusion, not only to improve access but to build environments in which we all thrive together. To look through the lens of “you,” and to design from empathy and mutual care, is the foundation for the kind of inclusive design that must now take root. It is no coincidence that this theme is being explored in Gwangju. The city is a symbol of democracy, equality, solidarity, and inclusion. As the name “Mudeung” suggests (“no ranks”), no one is higher or lower than another; Gwangju has long embodied a philosophy of shared dignity. I wanted to place design on top of this cultural spirit. If Korea seeks a more central role in global design discourse, it must go beyond tools and aesthetics and offer philosophy, questions, and reflection. In that sense, “YOU, THE WORLD” marks a starting point for Asia’s next step: an emotional expansion, a search for identity, and a deeper form of global solidarity grounded in design.

Gwangju as a city and the biennale format itself are both powerful symbols of inclusion. While Korean designers are increasingly visible on the global stage, some argue that a distinctive design identity has yet to emerge. From your perspective, what defines the DNA of Asian design, and how should it be nurtured moving forward?

Gwangju may not be widely known as a design city, and that is precisely its strength: it can ask fundamental questions about what design truly is. Through this Biennale, I wanted to translate the spirit of Gwangju into a design language, especially the egalitarian values symbolized by Mudeungsan Mountain. Gwangju has long been rich in culture, art, and historical consciousness. If design reflects society and culture, then Gwangju offers fertile ground for deep and meaningful discourse. Asking questions that resonate with the spirit of the times is, in essence, a path toward understanding the identity of Asian design.

The DNA of Asian design cannot be reduced to a single code. Asia is not a monolith; it is a vast and evolving fusion of cultures and values. Its identity should be sought not in a single style but in attitudes and perspectives. I see three essential characteristics. First, human centeredness: Asian design traditions begin with lived experience, with life, emotion, and relationships at their core. Second, flexibility: Asia has long absorbed and integrated external influences while preserving its own values, creating forms of originality distinct from Western dualism. Third, emotional integration: Asian design rarely separates function and beauty, or tradition and modernity, or nature and technology. It tends instead to harmonize them, and this sensibility is one of its greatest assets.

There is still work to be done, especially in Northeast Asia and particularly in Korea, where a clear design identity has not yet been fully expressed. I attribute this to a culture of speed. Korea underwent rapid industrialization and digital transformation, and in that process the design field advanced by quickly adopting and adapting foreign influences. The result is a paradox. Korean design is admired around the world, yet few can clearly articulate what makes it uniquely Korean. Building identity is different from building speed or efficiency. What we need now is the courage to pause, reflect, and ask deeper questions. What can Korean design truly say to the world? The answer should begin with philosophy, not with form or technology. Just as Gwangju and Mudeungsan embody horizontal values and dignity, Korean design should embrace inclusion, humanity, and respect for difference. That is the core of identity to which we should aspire, not as fast followers, but as agenda setters who propose new discourse and new design languages. Platforms such as the Gwangju Design Biennale and the Asia Design Prize can help open the door to this transformation.

Asian countries have moved beyond the “fast follower” phase in the design industry. What steps must designers, educational institutions, and platforms take to become creative leaders with distinctive identities?

I believe the concept of the “fast follower” is deeply embedded in the design ecosystems of many Asian countries, including Korea. It has been a culture, and a strategy, centered on excellence in imitation and speed. In the early stages of industrial growth this approach proved highly effective. Korea’s IT, home appliance, and automobile sectors, for instance, rose to global prominence through quick and efficient execution. But design is not only about doing something better; it is about asking why it should be done at all. We are at a turning point where what matters is not speed but direction, not how well we follow but how clearly we question.

For too long, design education and industry have prioritized performance-oriented values. Schools emphasize employment-ready portfolios. Companies prioritize products and services that sell quickly. Within such structures, designers are trained to solve existing problems more efficiently rather than to redefine them. The risk is clear: without strong identity and creativity, even brilliant design becomes replaceable. If your work is only “slightly better,” it will be overtaken by the next fast follower. We are already seeing this in real time. To break the cycle we must shift from fast followers to agenda setters, those who initiate the questions that matter. This does not mean inventing new buzzwords or chasing flashy aesthetics. It means cultivating the capacity to ask:

Why is design needed in our era? What emotions and issues are we responding to?

And then comes the harder work: building a sustained language, attitude, and discourse around those questions. Schools should train students not only to supply answers but to frame deeper questions. Design platforms, especially international awards such as ADP, should act not only as evaluators of excellence but as forums for critical discourse. They should spotlight works that offer the clearest and most compelling responses to the essential design questions of our time.

I see immense value in the role a platform like ADP can play. Its structure gathers a wide range of design works rooted in pan Asian sensibilities, philosophies, and social contexts. With this accumulated body of work, ADP can begin to read not only where design stands today but where it is headed. Such an archive is more than a list of winners; it becomes a topographic map of creativity itself. For Asia to lead creatively, it does not need faster technology or more intricate forms. It needs deeper reflection, more resilient values, and more persuasive philosophies embedded in design. To achieve that, industry, academia, and platforms must work together, not simply to promote design, but to design new questions in common. Now is the right moment to begin that shared inquiry.

The 2025 Gwangju Design Biennale marks its 11th edition, an important milestone. What do you see as this year’s most significant focus or strategic distinction?

The 11th Gwangju Design Biennale is not a repetition of past iterations; it is a moment of redefinition. With a decade of accumulated experience, we now stand at a turning point that asks us to reconsider not only the exhibition format but its essence. In the past, events like World Expos functioned as platforms for global exchange when international communication was limited. Today we live in an age of hyper-connectivity in which design images and outcomes are instantly accessible online. The exhibition’s role must therefore shift from simply showing what exists to guiding how we see, interpret, and reflect. This year’s Biennale begins from that perspective. Its most distinctive strategy is to cultivate the capacity to redefine design itself. Rather than treating the theme as a slogan, we have structured it as a comprehensive inquiry interwoven with social realities, technological advances, and philosophical discourse. “YOU, THE WORLD: How Design Embraces Humanity” serves as an integrated framework for how design should respond to the complexity of our time.

Another strategic focus is a multi-perspective structure. We designed the experience to be layered and inclusive for designers, citizens, industry leaders, policymakers, and educators. The goal is not to present design to the public but to invite people to experience and interpret it from their own standpoints. Visitors are encouraged to move beyond viewing finished outcomes and to take on an immersive, participatory role, becoming protagonists in the world that inclusive design seeks to build. This shift from a passive, viewer-based exhibition to an active, user-centered encounter is essential if we are serious about human-centered and inclusive design. In a time marked by global fragmentation, growing distrust, technological imbalance, and divided values, design must do more than produce visual beauty; it must help rebuild trust, bridge inequities, and offer practical models for how diverse communities can live well together.

It must offer meaningful connections between people, between people and technology, and between people and the environment. I believe this Biennale can become a testing ground for such design. And that testing ground gains even more meaning by being rooted in Gwangju. Like the spirit of Mudeungsan, which implies a place where no one stands above another, Gwangju symbolizes inclusion, dignity, and coexistence. These are exactly the values that today’s design must reclaim. Through this Biennale, we are posing vital questions:

What is the language that can truly connect our times? How can inclusion be practiced, not just spoken? Is technology helping us become more human, or less?

These are, I believe, the most strategic and meaningful propositions that the 11th Gwangju Design Biennale hopes to share with the world.

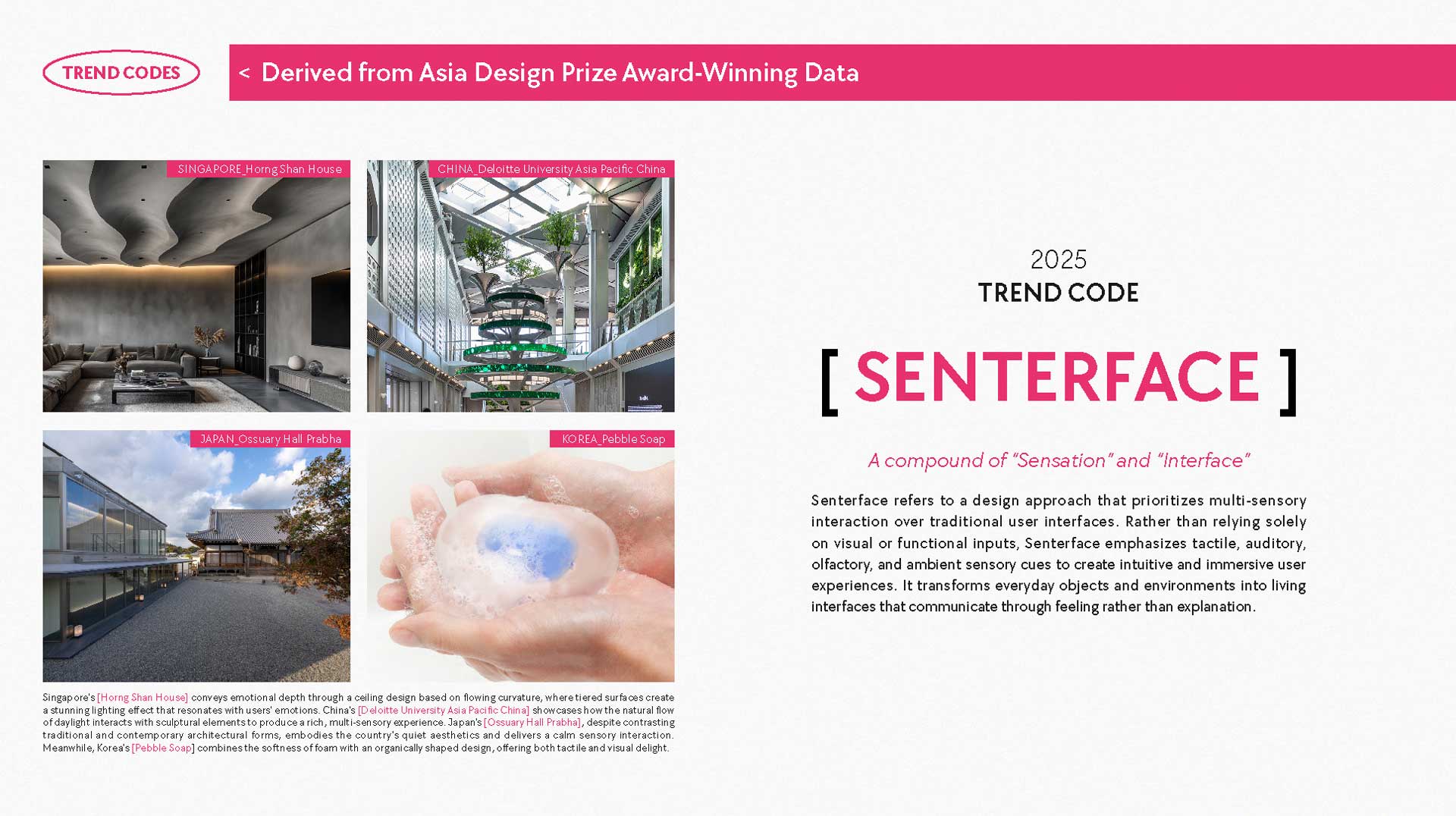

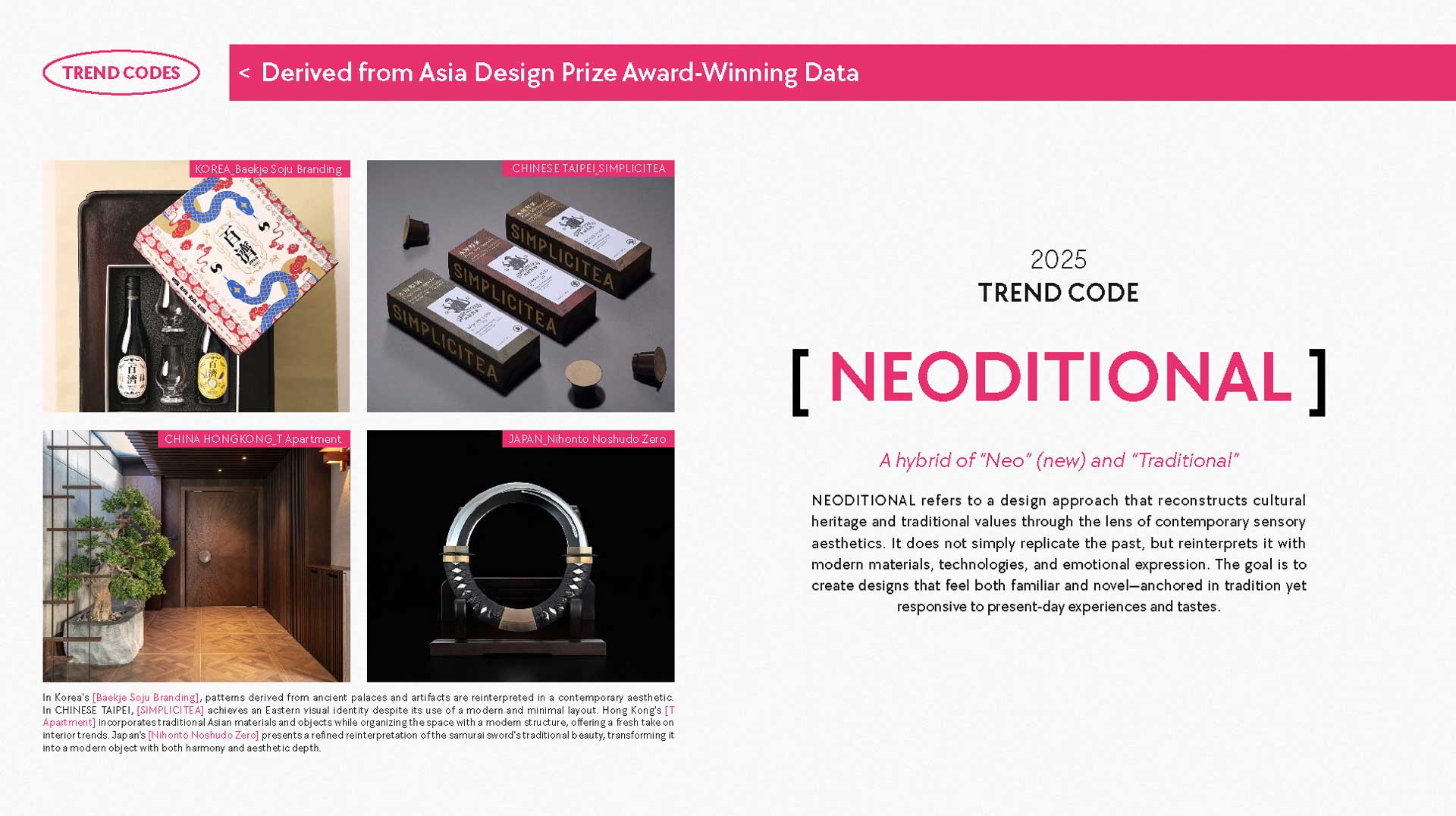

ADP has been creating coined terms like “Senterface” and “Neoditional” to capture emerging Asian design trends. What are your thoughts on this approach? And if you could propose a new term or concept for Asian design today, what would it be?

Creating new terms is a powerful way to express complex ideas in a condensed, memorable form. Words such as Senterface or Neoditional carry layered meanings that are hard to explain otherwise, which makes them useful in design because the field is inherently contextual and multidimensional. In that sense, ADP’s ongoing experiments with language play a vital role in structuring and archiving design trends. Still, a few questions are worth asking:

How often do we return to these terms after they are coined? Are they becoming fleeting trends rather than enduring vocabularies?

Especially in fast paced cultures like Korea and China, where the consumption of technology and culture moves at breakneck speed, keywords can quickly fade from memory. Think of terms like wellbeing, convergence, or the Fourth Industrial Revolution; these were central to government discourse just a few years ago but are now rarely mentioned. For coined terms to have lasting impact, they must be grounded in a philosophical and cultural context. It is not enough to create new terminology year after year; we should focus on identifying and nurturing sustainable values in design. One way to illustrate this is through the contrasting worldviews of East and West. In the West, nature has historically been seen as something to conquer. In the East, particularly in traditional Asian thought, nature is something to coexist with. Even when the same word is used, its underlying worldview can be profoundly different depending on its origin.

Rather than proposing a new buzzword, I would prefer to revive and reframe traditional Asian philosophical concepts as part of our design language. One such term that resonates deeply with me is “共鳴 (Gongmyeong),” or resonance. It is not just a response; it is a relational sensitivity, an awareness of the other, and the capacity to vibrate in harmony. Design also creates emotional impact through resonance with the user. I believe resonance could become a guiding value in the future of Asian design. In short, language is essential only when it carries lasting meaning beyond trends. Neologisms are effective tools, but their value lies less in the act of naming and more in the spirit that gave rise to them. If a platform like ADP introduces a new key term each year, I hope it does so not to chase novelty, but to invite deeper reflection on the ideas, values, and futures embedded in that term. Only then can language transcend trend cycles and become a true part of our design heritage, accumulated, passed on, and remembered.

Despite the growing presence of Korean designers on the global stage, many still feel that Korean design lacks a clearly recognizable identity. From your perspective, where do you think the true identity or strength of Korean design could begin to take shape?

The question of Korean design identity is not merely about visual styles or aesthetic preferences. I believe it must begin with a more fundamental inquiry: Why do we design at all? After the Korean War, Korea embraced design largely under American influence, adopting it as a tool to support rapid industrialization and economic growth. While this approach helped design become strategically useful, it also left little room to develop a deeper philosophical understanding of what Korean design could represent. Yet Korean culture is rich with its own sensibilities and ways of thinking. Consider expressions like dadaikseon (more is better), iwangimyeon dahongchima (if it is the same, choose the more vibrant one), or the well known love of bold and complex flavors, with spicy, sour, sweet, and salty appearing all at once. These phrases reveal an aesthetic rooted in richness, complexity, and emotional abundance. There is also a uniquely Korean social attentiveness captured in the word ojirapeu, which reflects a proactive concern for others and is deeply embedded in communal life. These cultural sensibilities have powered the global appeal of Korean content, from K-pop to K-dramas, and they could also inform a unique design philosophy.

The problem is that this cultural wealth has not yet been fully translated into design frameworks or philosophies. Korean design remains largely tied to performance-driven market logic that prizes speed, technical superiority, and efficiency. Designers are trained to solve existing problems well, not to pose new questions. As a result, Korean design is often seen as universal yet short on originality—technically excellent, but lacking a clear, distinctive voice on the world stage. Now is the time to redefine what Korean design truly stands for, and doing so requires courage. We need to step away from the race for speed long enough to ask where we are heading. In design education, we must move beyond teaching how to make things better and encourage students to ask why something should be designed in the first place. In industry, we must stop reacting only to market needs and begin to build strategies grounded in long-term thinking, cultural context, and social responsibility.

Design awards platforms like ADP also have a critical role to play. If ADP can provide space to explore, showcase, and discuss the unique identity of Korean design, these ongoing dialogues can serve as the foundation for a more authentic and lasting design philosophy. Ultimately, design identity isn’t built overnight. It’s the product of asking difficult questions, experimenting boldly, failing meaningfully, and learning deeply over time. And I believe we are now standing at the starting line of that journey.

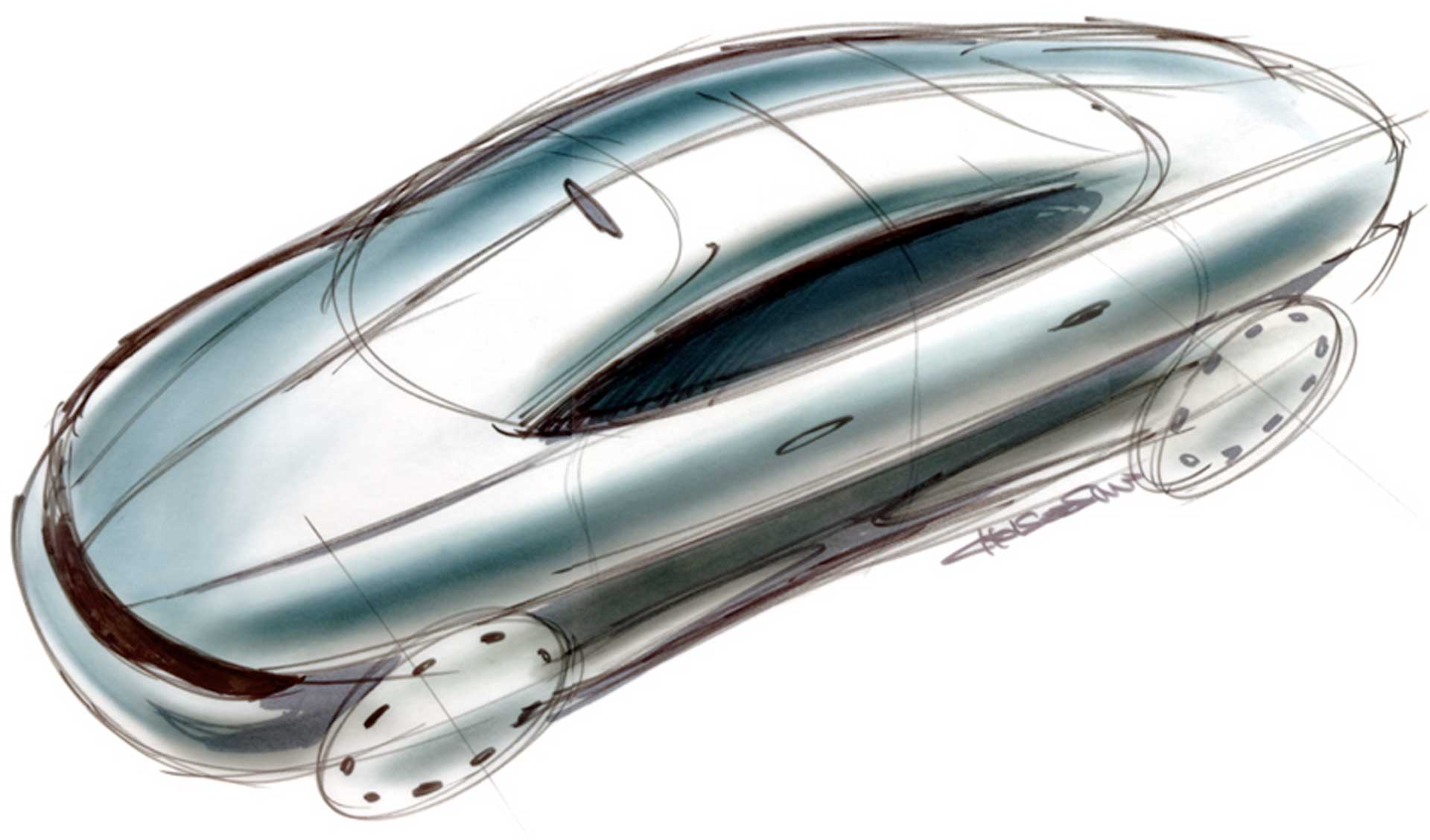

You’ve previously been deeply involved in design strategy for major Korean automotive brands. How has your experience in the automotive industry influenced the curatorial direction of the Gwangju Design Biennale and its dialogue with platforms like ADP?

Automotive design is more than product design; it is a complex discipline that synthesizes mobility, emotion, technology, and the human experience. In my own work I have always prioritized not the exterior beauty of the car but how people feel inside a moving space. In that sense I would describe it less as “car design” and more as “designing a lifestyle through the automobile.” That perspective naturally aligns with the philosophy of inclusive, human centered design. Before it is a physical form, design is a trigger for emotional response and a vessel of memory. Just as we do not perceive a person as a mix of proteins and water, we do not see a car as merely steel, plastic, and rubber. We sense its values, character, and symbolic meanings. I have applied the same lens to the Gwangju Design Biennale, moving beyond form and function to explore how design gives rise to new values, new ways of living, and new forms of connection.

There is also a useful parallel with the idea of “Legacy Beyond Asia.” A car is not only a machine; it is a cultural artifact, a capsule of its era and its people. In the same way, the legacy that Asian design leaves on the global stage should not be limited to aesthetic appeal or technical excellence. It should reflect deeper questions: what kinds of mobility we envision, which sensory experiences we design for, and what forms of human connection we value. The answers to these questions form the foundation of the newness we must create.

ADP MEDIA’s slogan, “Legacy Beyond Asia,” aims not just for aesthetic excellence, but for expanding a culturally grounded design language. In your view, what kind of legacy should Asian countries strive to leave for the next generation through design?

The phrase “Legacy Beyond Asia” carries an ambitious vision that reaches beyond geographic boundaries. To me it is not merely a slogan; it is a declaration that design originating in Asia should move from consuming trends to setting the direction and standards of global design. I hope this slogan evolves into a structural message that reflects design’s cultural responsibility and philosophical depth. Asia today is no longer a peripheral player in the design world, nor simply a large market defined by population. It is increasingly a center of technological innovation, emotional sensibility, and social transition. The key challenge is to ensure that this momentum is not consumed as fleeting fashion but is passed down as sustainable values to the next generation. Two words capture the essence of this responsibility: identity and relationality. Identity is about understanding why we exist. Relationality is about asking how that identity connects with others.

Design is a language that records its era and a grammar that links generations. What we must leave behind is not only form but a framework for thought. The true legacy lies not in what we design, but in why we design the way we do: the philosophy and rationale that inform every creative decision. That is when design becomes culture, education, and ultimately heritage. This is where “Legacy Beyond Asia” finds its relevance. If ADP grows into a platform that not only selects winners but also encourages designers to articulate the context and philosophy behind their work, it will hold value far beyond awards. Design is, at its core, the practice of asking questions and seeking answers. Perhaps the most important legacy we can leave for future generations is not the question “What should we make?” but the question “What values should we pursue?” If ADP becomes the platform that boldly poses and supports this inquiry, its impact will be both timely and enduring.