You are walking through the transfer corridor at Gangnam Station. Moving quickly with hundreds of others to change from Line 2 to the Shinbundang Line, dozens of brands flash past on the digital billboards lining both sides. Cosmetics, delivery apps, fashion labels, financial products. You have no memory of consciously seeing any of them. And yet, a month later, you find yourself hesitating in front of an Olive Young shelf. A product that feels unfamiliar, yet somehow familiar. Where have I seen this before? You cannot remember, but your hand has already reached for it. This is not someone else’s story. It is my own.

But is this really just my experience? The first item I bought raised an immediate question: where had I seen it before, and why did it not feel unfamiliar? This is not a coincidence. It is the unsettling power of the priming effect at work. While working on a subway advertising campaign design project for a beauty brand, our team encountered an intriguing question. Do people actually look at subway advertisements? Or more precisely, can advertisements that are not consciously noticed still be effective? The answer was surprising. They are effective even when they are not consciously perceived, or perhaps precisely because they are not. The human brain processes approximately 11 million bits of information per second, yet the amount we consciously register is only about 40 bits. What happens to the rest? It enters the unconscious, quietly stored away. During those three seconds in the Gangnam Station transfer corridor, your conscious mind is focused on one thing: I need to hurry. But your brain has already scanned and stored the brand logos, colors, and messages on the digital billboards.

This is the priming effect, a phenomenon in which previously exposed stimuli unconsciously influence later judgments and behavior. According to research by psychologist John Bargh, after being exposed to certain words or images, people recognize related concepts more quickly and evaluate them more positively, often without realizing they have been influenced at all. Seoul Subway Line 2 serves an average of 2.5 million passengers a day. From Samseong Station to Gangnam Station takes about three minutes, during which commuters pass an average of twelve digital advertising screens. Each ad is visible for roughly 0.8 seconds, not even a full second. Yet those brief exposures can shape a purchasing decision weeks later. On the subway ride home after work, you are exhausted, absentmindedly staring at your smartphone. You scroll through office group chats and social media feeds without thinking. Your conscious attention is on the screen, but in your peripheral vision you catch Baemin’s distinctive typography. It is after work. Your brain automatically makes the connection. Baemin equals dinner. Hunger has already begun.

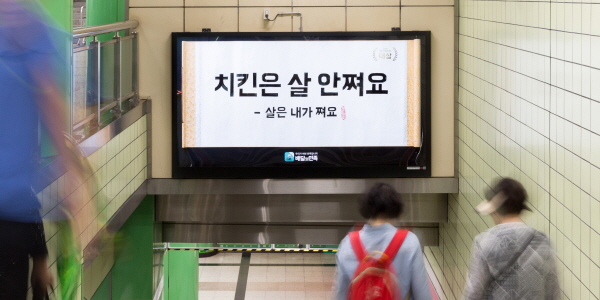

You do not register that you have ‘seen’ the advertisement. Your gaze remains fixed on your phone screen. But your brain has already begun to work. You arrive home, and the thought of dinner rises almost automatically. You pick up your phone. The apps on your home screen come into view. Your finger taps Baemin without hesitation. You cannot really explain the choice. It simply feels familiar, something you reach for without thinking, like habit. But the real reason is simpler and deeper. Just moments earlier on the subway, your brain had already formed the association dinner equals Baemin. Before conscious thought could intervene, the unconscious had already made the choice. Baemin’s strategy is highly deliberate. Their ads are concentrated at major stations between 6 and 8 p.m., the exact window when people begin to think about dinner. And notably, they never show food. Images of fried chicken or pizza would actually work against them, because anyone not craving chicken would simply tune the ad out.

Instead, they sell context. The time called dinner, the brand called Baemin, and their distinctive typography. When these three elements are repeatedly linked, the brain naturally constructs the equation dinner equals Baemin. This is contextual priming. By repeatedly exposing a brand within a specific situation, the brand is automatically recalled when that situation reappears. You saw that typography every day for two weeks. Consciously, you never once thought, this is a Baemin ad. But your brain behaved differently. Same time, same context, fourteen exposures. The unconscious had already finished learning. Now you are walking through Seongsu. You are not heading anywhere in particular, just taking a stroll. Suddenly, your steps slow in front of one store. Gentle Monster. There are no glasses in the window. Instead, a massive silver sphere rotates slowly, while unfamiliar sculptural forms float around it. You open the door and walk in. Why? You do not know. You were simply drawn in.

Let us rewind three weeks. Lying in bed before sleep, you scroll through Instagram. An influencer you follow has posted about visiting a Gentle Monster store. Surreal interiors, intense purple lighting, objects of unclear purpose. The space draws your attention more than the eyewear itself. For half a second, you think, Where is that place? Then you scroll on. You forget. Or rather, you think you forgot. Gentle Monster’s strategy is the opposite of Baemin’s. Where Baemin creates a clear associative link, Gentle Monster creates cognitive incompleteness. The brain dislikes incomplete information. When a question such as What is this? remains unanswered, it lingers in the unconscious. In psychology, this is known as the Zeigarnik effect, the tendency to remember unfinished tasks more vividly than completed ones.

Over three weeks, you encounter that space seven times. Other influencers, friends’ stories, again and again Gentle Monster appears. Each time you think, Where is that place? and move on. But your brain retains the unanswered question. And when you finally encounter the physical store in Seongsu, your feet stop. You do not realize that this curiosity began weeks earlier on your feed. You simply experience it as spontaneous interest. Once inside, the surreal atmosphere you saw online unfolds in real space. At this moment, your brain experiences a distinct sense of pleasure. When incomplete information is finally resolved, dopamine is released. This is not just shopping. It is cognitive closure. It is the moment your brain has been anticipating for weeks, the moment the question is answered.

The reason the priming effect is unsettling is that we cannot consciously control it. The people who believe they are not influenced by advertising are often the most influenced, because their defenses are down. Information that never enters conscious awareness bypasses critical thinking and goes straight into the unconscious. As designers, what we must consider is not simply visuals that stand out. It is the elements that quietly seep into the unconscious. Should we create a clear brand signature like Baemin’s typography, or leave a sense of incompleteness like Gentle Monster that invites curiosity? The strategies differ, but the goal is the same: to imprint on the unconscious through fleeting exposure.

What truly matters is repetition. A single exposure leaves only a trace. Daily exposure over two weeks turns that trace into memory. Even while believing you have never seen the brand before, your brain has already classified it as familiar. Understanding the priming effect gives us two things. Designers can create more strategic communication, choosing whether to connect context through clarity or to spark curiosity through incompleteness. Consumers can become more aware of their unconscious choices and make more deliberate decisions. The next time you take the subway, try consciously looking at the advertisements. Notice which brands, which colors, which messages are repeated. Then, a month later, observe what you buy. The choice may already be made, but understanding how it was made can make your mind just a little freer.