As 2025 draws to a close, this moment of reflection on the past year and preparation for what comes next naturally invites a series of questions: What have we made, and what have we learned? As Albert Einstein suggested, learning is a process of understanding the present through the past, and as John Dewey emphasized, experience gains meaning not in itself but through the attitude of reflection applied to it. This kind of reflection has become even more critical in today’s environment surrounding architecture and design, especially as AI has moved to the forefront of creative production. AI demonstrates astonishing speed and volume in generating images and forms. With just a few lines of prompts, outputs evoking specific styles can be produced endlessly. Yet at this point, we are compelled to ask again: is this creation a reference, or merely a sophisticated form of copying?

In the field of design, copying has long been considered a clear taboo. Originality is the lifeblood of design, and the moment a form or image is directly replicated, the work loses its persuasive power. In architecture, by contrast, referencing and reinterpreting historical buildings or urban contexts has been more naturally accepted. This is because architecture is not a singular outcome, but a cultural record accumulated, adapted, and transformed over time and place. This difference is something the author has felt most acutely through studying both design and architecture. In fact, when first encountering the concept of reference in architecture, it was not easy to accept. Looking at other architects’ works felt uncomfortably close to copying, and it was difficult to determine where learning ended and imitation began.

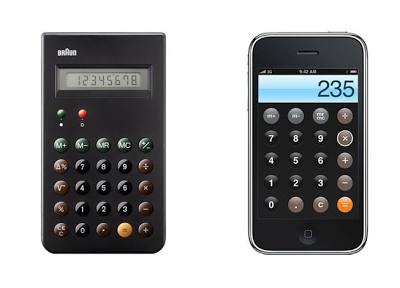

However, as the study deepened, the understanding of reference gradually shifted. A reference is not an act of borrowing form, but a process of reading the background from which a building emerged. This includes its history and culture, technology and industry, and the social questions it addresses. It also became clear that without properly studying references, one is more likely to fall into the easiest trap of copying surface forms alone. This distinction is repeatedly confirmed in both design and architecture. Apple did not simply replicate the minimalism of Germany’s Braun design. Instead, it referenced the underlying philosophy and combined it with user experience, technology, and the spirit of its time to develop an entirely different design language. By contrast, countless imitation products that merely mimicked appearance quickly disappeared from the market. Even when starting from the same point of departure, referencing a way of thinking rather than copying an outcome leads to fundamentally different results.

< Image source: Business Insider >

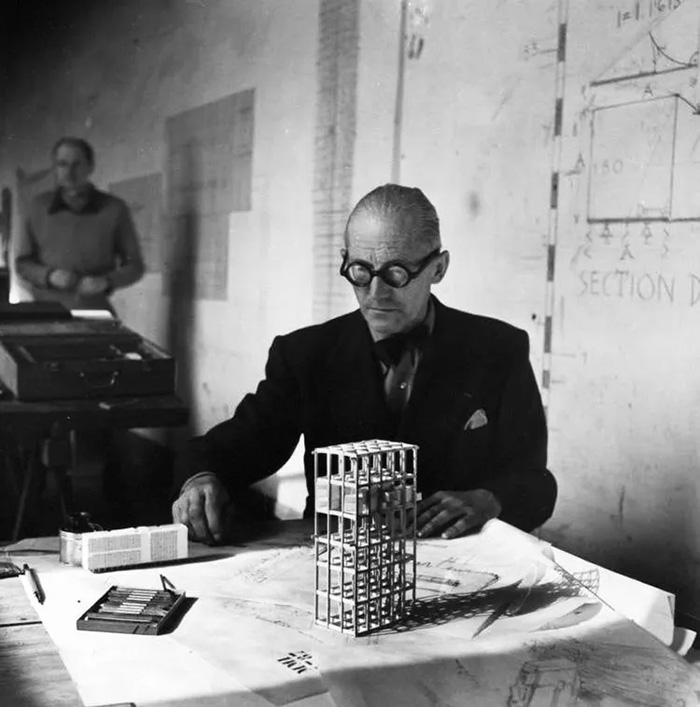

The same applies in architecture. The reason cases involving the unauthorized replication of Zaha Hadid’s architecture became controversial is that they were overt copies rather than references. While the curves and silhouettes may have appeared similar, the underlying design thinking that connects city, structure, and program was absent. By contrast, Tadao Ando openly acknowledges the influence of Le Corbusier, yet through a distinctly Japanese sense of space, light, and an attitude of silence, he established an entirely different architectural language. This is a clear example of how reference can lead to genuine creative transformation.

< Le Corbusier image source: PA >

< Image Source: The Japan Times >

Images generated by AI further blur this boundary. While AI can learn from vast accumulations of past outcomes and produce visually convincing forms, it bypasses the reasons those forms came into being. The questions, struggles, and failures embedded in the creative process are omitted. From the perspective of someone who has experienced both design and architecture, this represents a risky approach. It repeats outcomes while excluding the most critical phase of learning. This does not mean that AI should be rejected. AI is clearly a tool capable of expanding creative potential. The more important question is whether we use it as a machine that produces results on our behalf, or as a cognitive aid that enables deeper inquiry and interpretation. This choice is ultimately determined by our attitude toward distinguishing reference from copy.

In the end, what must be upheld in both design and architecture is clear. A reference is not about borrowing form, but about understanding structures of thought and context. Only through this process can copying truly be avoided. The author’s experience of studying both disciplines revealed not a strict boundary between design and architecture, but rather the points at which they are deeply interconnected. Understanding reference correctly proved to be the most critical point of departure in both fields. In the age of AI, architecture and design in Asia must become even more deliberate. Asia is a region shaped by layers of accumulated sense of place, material sensibility, industry and technology, and everyday culture. Images created without engaging with this context are easily consumed and quickly forgotten. By contrast, when Asia’s unique experiences and memories are responsibly referenced and reinterpreted, architecture and design from the region gain a distinct and resonant language on the global stage.

Amid the countless images and debates left behind by 2025, we now face a choice. Will we remain within the convenience of endlessly repeated copies, or move toward deeper thinking through reference? As we look ahead to 2026, one can hope it will be a year in which human interpretation and judgment, together with distinctly Asian creativity, emerge with greater clarity alongside advancing technology.