Enhancing one’s ability to see design begins with reading the engineering and functional logic hidden behind forms. Yet today’s designers are required to look beyond mere form analysis. They must ask expanded questions that encompass the entire life cycle of a product. While traditional industrial design focused on making and selling, contemporary design must ensure that products retain meaning even after disposal, within a sustainable loop. Sustainability is no longer an optional aesthetic or functional consideration—it is a mandatory condition in legal and engineering design frameworks.

< Image Credit: Repair.eu, “Making Batteries Removable and Replaceable…” >

New legal standards, such as the EU battery regulation mandating removability, redefine the essential role of design. This goes beyond market trends: designing for longevity and minimizing waste is now a core requirement. Environmental responsibility should no longer be viewed as an add‑on—it must become the new starting point of creativity. If design is a process and a record of thought, then environmental obligations must now be included in that record. Sustainability is the most powerful strategic keyword in the future of industrial design.

Design Strategies for Extending Product Lifespan

< Image Credit: Logitech, Logitech Lift with replaceable battery module designed to extend product life and repair accessibility >

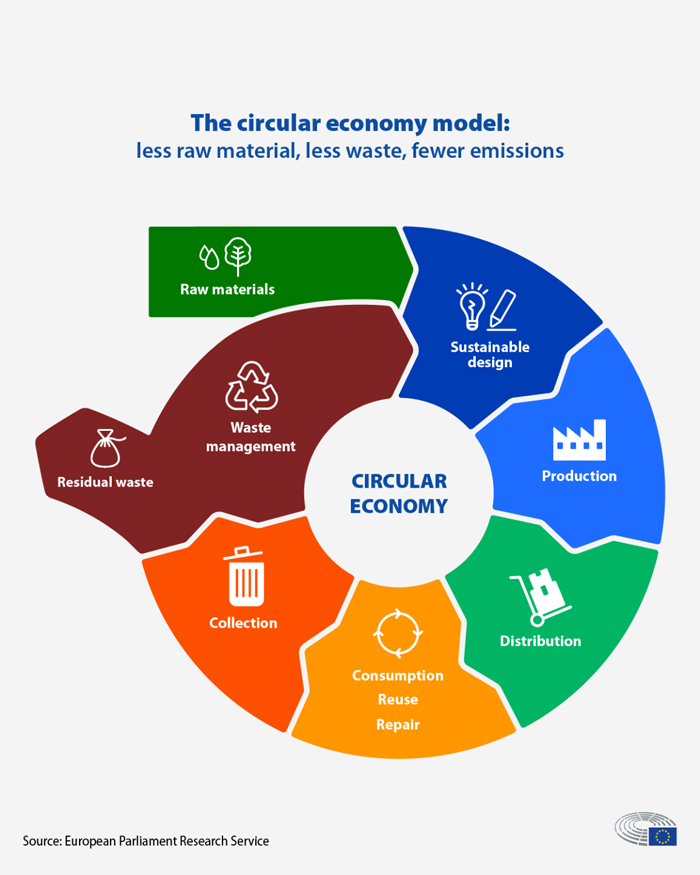

For decades, industrial design operated within a linear model—maximizing value at the point of sale, then discarding the product. Circular economy principles now demand that designers link a product’s end with a new beginning. Designers must go beyond surface aesthetics and instill logical responsibility across the product’s full life cycle. The circular model imposes four critical goals that fundamentally reshape product form, structure, and material:

• Maximizing Repairability: The EU’s “Right to Repair” obliges designers to create structures that are easy to disassemble and repair. Screw-based assemblies, minimal adhesives, and modular parts are no longer optional—they are required. This transforms products from disposable goods into long-term assets.

• Extending Usage Longevity: Materials that gain value over time deepen emotional bonds with users, naturally extending product life. Pursuing timeless design that transcends trends provides visual stability and sustained satisfaction—an effective strategy for curbing overconsumption.

• Facilitating Disassembly and Material Recovery: As products reach end-of-life, they must be designed for rapid and accurate material separation. Optimizing for single-material use and efficient separation of metals and plastics anticipates future recycling. Designers must craft material specification charts that minimize composites and increase purity, enabling recycled materials to return as high-quality components. This is one of the most critical engineering decisions in a circular economy.

The Invisible Forces Behind Form

Material is not merely a tool for expressing color or texture—it defines a product’s environmental responsibility and future regenerative potential. If form is the outcome of resolving design tensions, then material is the starting point that drives the entire process. Exceptional designers must now think like material scientists. Every material choice must answer the following questions:

< Image Credit: Model-Solution, CMF Lab >

1. Renewability

Substituting petroleum-based plastics with bio-based materials, recycled aluminum, or ocean waste plastics may impose form constraints. Yet it is the designer’s role to find compelling solutions within those constraints. Creativity born from environmental limitations is the essence of modern design.

2. Toxicity and Pollution Management

Materials should emit no harmful substances during manufacturing or disposal. This is not about choosing attractive materials—it’s about calculating environmental impacts across the full production chain. Responsibility now overrides aesthetic preference as a design imperative.

3. Supply Chain Transparency

Tracking a material’s origin, ethical standards, and processing history is now a baseline for premium design. Visualizing and managing the supply chain is part of the designer’s expanded role. Choosing ethically sourced materials can define a brand’s value.

From Form Givers to Circular Designers

< Image Credit: European Parliament Research Service, Circular Economy Concept Diagram >

Designers must now evolve into Circular Management Designers. Product design is no longer about making form—it is about envisioning and taking responsibility for the full lifecycle, from production to reuse after disposal. While new EU regulations pose challenges, they also provide designers with a powerful market rationale: sustainable design is competitive design. Only designers who understand the logic within form can transform environmental constraints into creativity—balancing aesthetics with responsibility. When design moves from eliciting “That’s beautiful” to asking “Why?”, it becomes a language, not an image. When sustainability is embedded in materials, design becomes a social promise, not just a product. Designers must now look not only at the present usage of products, but also at their future disassembly and regeneration. This is the only way to ensure that our designs become a responsible legacy for future generations. To read form is to read the future—of both humanity and the planet.