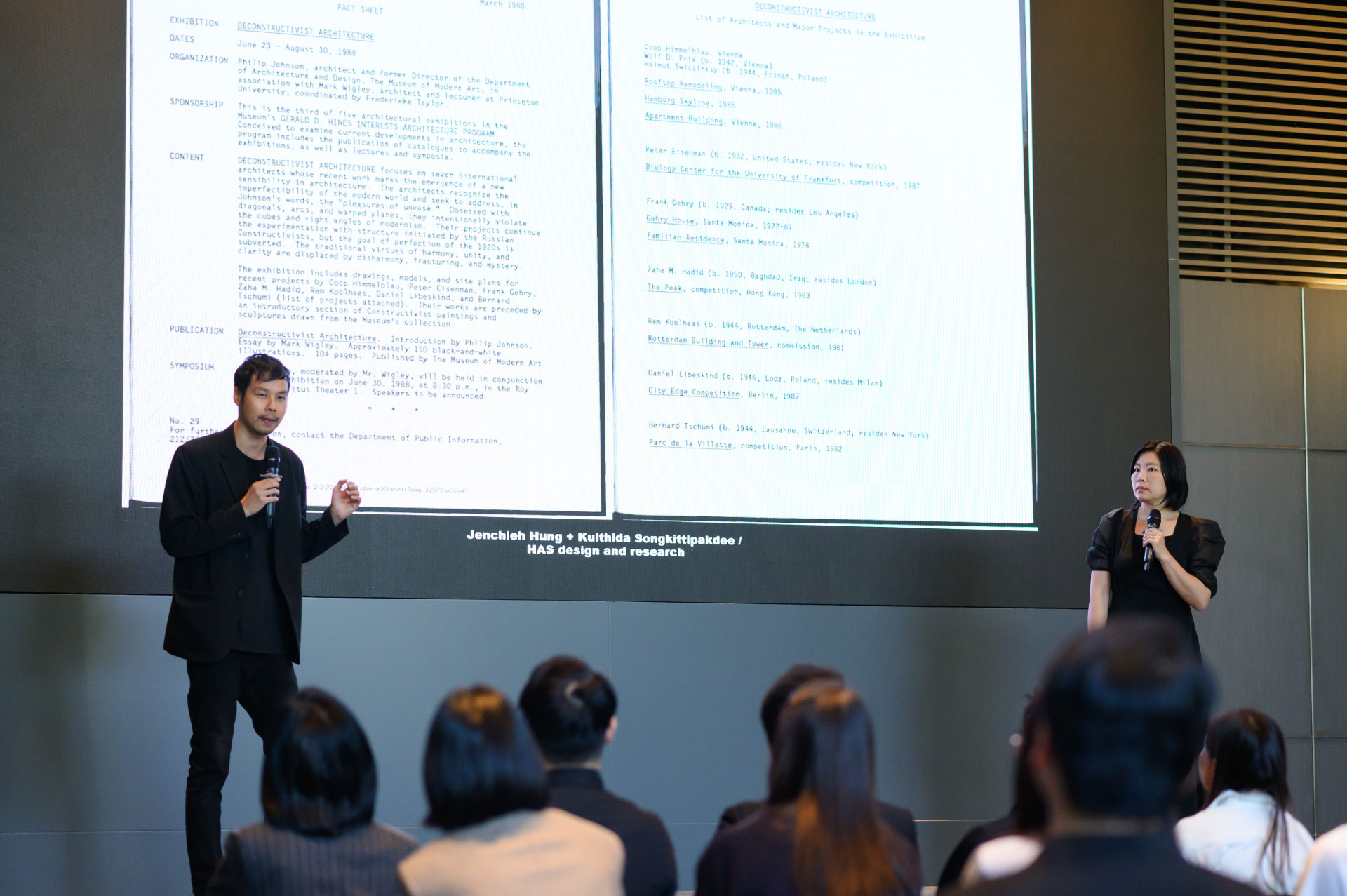

Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee Co-founders and Principal Architects, HAS Design and Research

“Architecture in Asia is often shaped by density, speed, and constant improvisation, and few practices translate these conditions into a clear design language as consistently as Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee, co founders and principal architects of HAS Design and Research. Working across Bangkok and Shanghai, they position design and research as parallel forces, tracing how informal urban scenes, material realities, and ecological questions can become architectural drivers rather than constraints. In this interview, they reflect on their idea of a new nature within the city, and on the conditions needed for more meaningful exchange across the Asian design landscape.”

To begin, could you introduce yourselves and share the core questions or concerns that led to the founding of HAS design and research?

We are Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee, architects, artists, educators, and the co founders and principal architects of the Thailand based firm Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS Design and Research, abbreviated as HAS Design and Research. The firm was founded out of a shared curiosity about how architecture can operate beyond the conventional boundaries of form and function. From the beginning, our core concern has been the relationship between architecture, context, and everyday life, exploring how design can respond sensitively to social, cultural, and environmental conditions while remaining conceptually rigorous. The firm’s name, HAS, derived from Hung and Songkittipakdee, reflects both the founders’ surnames and the concept of having, symbolizing the integration of research and design within our practice. It also expresses our interest in architecture as a process of accumulation, of ideas, histories, materials, and human experiences. We continually question how buildings can adapt, transform, and meaningfully engage with their surroundings rather than exist as isolated objects. Our research driven practice allows us to explore these questions through built work, academic inquiry, and experimentation across multiple scales.

HAS design and research emphasizes a parallel approach of design plus research. How do these two tracks operate within a project, and at what point do they converge into a single architectural outcome?

At Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS Design and Research, design and research operate as parallel and equally important processes throughout each project. Research does not function as a preliminary phase that concludes once design begins. Instead, it continuously informs and challenges design decisions from start to finish. Each project begins with a careful investigation of context, including social patterns, cultural narratives, environmental conditions, and material possibilities. These inquiries help us frame the fundamental questions of the project rather than immediately pursuing formal solutions.

You often speak about the idea of a “new nature” or “nature within the city.” What does this concept mean to you, and how does it function as a design criterion in your work?

The idea of a “new nature” or “nature within the city” from our firm, Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS Design and Research, reflects our belief that architecture can reintroduce natural systems into dense urban environments, creating spaces that are both ecologically sensitive and experientially rich. Rather than viewing nature as something separate from the city, we see it as a set of forces, patterns, and processes that can be integrated into architectural design. This approach encourages us to consider light, air, water, vegetation, and seasonal changes as active components of spatial experience.

In practice, this concept serves as a critical design criterion. It guides how we shape volumes, openings, circulation, and materiality to foster meaningful connections between people and their surroundings. By embedding natural rhythms and ecological strategies into the urban fabric, we aim to create architecture that supports both environmental sustainability and human well being. Each project becomes an opportunity to reinterpret what nature can be within the city, as a dynamic, living system that coexists with architecture and urban life, rather than being relegated to parks or isolated landscapes. Through this lens, the city itself becomes a stage for new forms of ecological and social interaction.

Keywords such as THE improvised, MANufAcTURE, and Chameleon Architecture appear frequently in your discourse. What kinds of Asian urban scenes did these concepts originate from, and why do you believe they remain relevant today?

The concepts of THE improvised, MANufAcTURE, and Chameleon Architecture emerge directly from the dynamic and often unpredictable urban environments of Asia. In many Asian cities, rapid growth, dense populations, and shifting economies create informal, adaptive, and hybrid architectural landscapes. Buildings are continuously modified, repurposed, or extended by their users, revealing a culture of improvisation that challenges conventional architectural hierarchies. THE improvised reflects this flexibility, describing designs that anticipate change and allow spaces to evolve organically over time.

MANufAcTURE emphasizes the intersection of making and inhabiting, where construction, production, and daily life converge through layered urban activities. Chameleon Architecture describes buildings that adapt visually, functionally, or socially to their surroundings, blending with diverse contexts while responding to cultural, environmental, and economic conditions. These concepts remain relevant because Asian cities continue to grow and transform at unprecedented speeds. Architecture that embraces adaptability, responsiveness, and hybridity becomes essential for sustaining vibrant urban life. By observing and learning from these improvisational strategies, our work seeks to create designs that are not only resilient, but also culturally and socially meaningful, capable of evolving alongside the cities they inhabit.

Your research explores temporary and informal urban conditions such as railway markets, street vendors, and illegal structures beneath elevated highways. How do these observations influence form, material choices, and spatial programming in your architecture?

Our studies of temporary and informal urban conditions, such as railway markets, street vendors, and structures beneath elevated highways, offer vital lessons for architectural design. These spaces demonstrate resilience, adaptability, and an efficient use of limited resources, revealing strategies that conventional architecture often overlooks. By observing how people appropriate and transform space, we gain insights into circulation, flexibility, and human scale interactions, which directly inform our spatial programming and how we prioritize everyday use. Material choices in our work at Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS Design and Research are often inspired by the improvisational, lightweight, and easily assembled or disassembled constructions found in these informal settings.

We aim to balance practicality with durability, allowing architecture to adapt to changing needs without compromising aesthetic or structural integrity over time. Form emerges from a careful reading of context, reflecting both functional requirements and the dynamic energy of these urban environments, rather than forcing a fixed shape onto living conditions. Ultimately, these observations encourage us to design architecture that is responsive, inclusive, and open ended. By embracing impermanence, hybridity, and user participation, our projects create spaces that not only accommodate but also empower urban life, transforming ephemeral urban phenomena into meaningful and inhabitable experiences.

HAS design and research projects are often noted for synthesizing form, pattern, material, and technology into singular and irreducible constructions. When integrating these complex elements into one architectural language, what principles do you consider most essential?

Yes, at Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS Design and Research, synthesizing form, pattern, material, and technology into a coherent architectural language begins with a careful reading of context and program. We treat each element as interdependent rather than separate, so the architecture can remain both functional and expressive, without one aspect overpowering the others. Key principles include integration through clarity, adaptability to changing uses and conditions, and close attention to human scale and tactility. Every decision is expected to serve multiple purposes simultaneously, balancing structural, environmental, and experiential considerations in a way that feels intentional rather than layered on. By embedding complexity seamlessly and by maintaining consistency across systems, our projects produce singular and irreducible architecture that is rigorous, responsive, and capable of engaging meaningfully with its surroundings.

Your portfolio spans cultural buildings, religious architecture, exhibitions, and installations across varying scales. What sensibility or attitude remains consistent across these diverse project types?

Both of us, Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee, prioritize adaptability, allowing spaces to respond to changing uses, environmental conditions, and community engagement. This attitude is reflected in careful attention to circulation, spatial hierarchy, and tactile qualities, ensuring that architecture resonates with its users and supports the way people actually move, gather, and inhabit a place. Even in highly experimental or ephemeral installations, the same principles of rigor, responsiveness, and thoughtful materiality apply, creating experiences that are both poetic and functional, and that remain grounded in the realities of use.

Ultimately, our work seeks to balance intellectual inquiry with lived experience, producing architecture that is sensitive, immersive, and socially meaningful. By maintaining these core values across contexts and scales, we establish a unified approach that connects seemingly disparate project types, ensuring that each is rooted in the same careful and human centered design philosophy.

Both of you are deeply involved in education, curation, and professional organizations. As practitioners and educators, what critical questions do you believe contemporary Asian architecture must continue to address?

As practitioners and educators, both of us have been invited to serve as jurors for the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) – RIBA International Awards Asia Pacific Awards, and have held appointments such as Lifetime Honorary Professor at Kunming University of Science and Technology, Visiting Professor at Tongji University, Visiting Professor at Chulalongkorn University, Adjunct/Visiting Professor at King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, and most recently, Jenchieh Hung as Distinguished Professor at Huaqiao University. We, Jenchieh Hung and Kulthida Songkittipakdee, believe contemporary Asian architecture must continuously engage with questions of adaptability, social responsibility, and cultural relevance, especially as the region undergoes rapid transformation.

Rapid urbanization, climate change, and shifting societal needs demand architecture that is not only visually compelling but also environmentally sensitive and socially inclusive, with real accountability to people’s everyday lives. Critical questions include how architecture can respond to dense and informal urban conditions, how it can balance tradition and innovation without reducing either to a surface gesture, and how it can integrate ecological strategies without compromising human experience. We also consider how design can accommodate impermanence, hybridity, and collective participation, reflecting the lived realities of Asian cities while fostering meaningful connections between people and place.

Through education, curation, and professional engagement, we explore these questions in both theoretical and practical contexts. By encouraging students and professionals to think critically about context, materiality, and social impact, we aim to cultivate architecture that is resilient, adaptive, and culturally rooted. Ultimately, contemporary Asian architecture should not only address functional and aesthetic concerns, but also contribute to creating sustainable, inclusive, and vibrant urban life.

Working primarily in Bangkok and Shanghai, your designs inevitably engage with local conditions such as climate, materials, labor, and regulatory systems. How does HAS transform these local constraints into creative drivers?

We treat local conditions such as climate, materials, labor, and regulations as opportunities rather than constraints. Working in Bangkok and Shanghai, we study environmental patterns such as light, ventilation, and seasonal shifts, and translate them into spatial strategies that enhance comfort and human experience in a direct and measurable way. Rather than applying a universal solution, we begin by reading how each city behaves, how heat accumulates, how air moves, and how people occupy space across different times of day and seasons, and then we allow those realities to guide the architecture.

Locally available materials and construction methods inform both aesthetics and technical solutions, allowing our buildings to feel grounded in their context while also remaining precise in execution. In many cases, material availability, fabrication capacity, and on site craftsmanship become part of the design logic, shaping details, tolerances, and tectonic expression, instead of being treated as secondary considerations. Regulatory and urban limitations also often inspire inventive approaches, encouraging flexibility, hybrid uses, and adaptive forms that can work within constraints without losing conceptual clarity. By embracing these local realities as creative drivers, our firm, Jenchieh Hung + Kulthida Songkittipakdee / HAS Design and Research, produces architecture that is responsive, inventive, and deeply connected to the social and environmental fabric of each city.

Looking ahead, what kinds of efforts and movements do you think are necessary to strengthen solidarity and exchange within the Asian design market? Based on your experience, what conditions would enable meaningful collaboration beyond national and regional boundaries?

Architecture and design in Asia are remarkably diverse, reflecting a wide range of cultural, social, and environmental contexts. This diversity is a strength, but it can also become a barrier if exchange remains limited to national or regional frameworks. At the same time, there is immense potential for mutual learning, particularly in how Asian cities address rapid urbanization, environmental pressures, social density, and material innovation. Many of these challenges are shared across the region, even if they manifest differently in each local context.

From our experience, design itself serves as the most powerful language for communication across borders. A well conceived design can convey culture, history, and social values without relying solely on words, enabling people from different backgrounds to understand and engage with one another. To strengthen solidarity, we believe there must be more platforms for open exchange, such as cross regional exhibitions, research driven collaborations, academic networks, and professional forums that encourage long term dialogue rather than short term visibility. Meaningful collaboration emerges when there is mutual respect for local specificity alongside a willingness to learn from different perspectives. Conditions such as shared research agendas, transparent processes, and sustained relationships between institutions, studios, and educators can help move Asian design discourse beyond comparison toward collective growth. Ultimately, solidarity within the Asian design market will be built not through uniformity, but through thoughtful exchange that values difference while recognizing common ground.